Published according to Kevin Simler’s guidelines. [1] Simler describes his website as “a collection of essays about philosophy, human behavior, and occasionally software.”

I discovered this only last week, but I wish I had discovered it earlier! — R. D.

Contents

- Introduction

- Truth in advertising

- Underhanded advertising

- Ad examples

- Conspicuity

- Product types

- Why aren’t brands two-faced?

- Absence of personal advertising

- No immunity

Introduction

There’s a meme, particularly virulent in educated circles, about how advertising works — how it sways and seduces us, coaxing us gently toward a purchase.

The meme goes something like this:

Rather than attempting to persuade us (via our rational, analytical minds), ads prey on our emotions. They work by creating positive associations between the advertised product and feelings like love, happiness, safety, and sexual confidence. These associations grow and deepen over time, making us feel favorably disposed toward the product and, ultimately, more likely to buy it.

Here we have a theory — a proposed mechanism — of how ads influence consumer behavior. Let’s call it emotional inception or just inception, coined after the movie of the same name [2] where specialists try to implant ideas in other people’s minds, subconsciously, by manipulating their dreams. In the case of advertising, however, dreams aren’t the inception vector, but rather ideas and images, especially ones which convey potent emotions.

The label (“emotional inception”) is my own, but the idea should be familiar enough. It’s the model of how ads work made popular by Mad Men, and you can find similar accounts all across the web. A write-up at the Atlantic, for example — titled “Why Good Advertising Works (Even When You Think It Doesn’t)” — says that

advertising rarely succeeds through argument or calls to action. Instead, it creates positive memories and feelings that influence our behavior over time to encourage us to buy something at a later date. [3]

“The objective [of advertising],” the article continues, “is to seed positive ideas and memories that will attract you to the brand.”

Lifehacker echoes these ideas in an article intended to help readers mitigate the effect of ads. “An ad succeeds at making us feel something,” it says, “and that emotional response can have a profound effect on how we think and the choices we make.” [4]

This is a decidedly Pavlovian account of ad efficacy. Like Pavlov’s dogs, who learned to associate the ringing of a bell with subsequent food delivery, humans too can be trained to make more-or-less arbitrary associations. If Coke shows us enough images of people beaming with joy after drinking their product, we’ll come to associate Coke with happiness. Then, sometime later, those good vibes will come flooding back to us, and we’ll be more likely to purchase Coke.

This meme or theory about how ads work — by emotional inception — has become so ingrained, at least in my own model of the world, that it was something I always just took on faith, without ever really thinking about it. But now that I have stopped to think about it, I’m shocked at how irrational it makes us out to be. It suggests that human preferences can be changed with nothing more than a few arbitrary images. Even Pavlov’s dogs weren’t so easily manipulated: they actually received food after the arbitrary stimulus. If ads worked the same way — if a Coke employee approached you on the street offering you a free taste, then gave you a massage or handed you $5 — well then of course you’d learn to associate Coke with happiness.

But most ads are toothless and impotent, mere ink on paper or pixels on a screen. They can’t feed you, hurt you, or keep you warm at night. So if a theory (like emotional inception) says that something as flat and passive as an ad can have such a strong effect on our behavior, we should hold that theory to a pretty high burden of proof.

Social scientists have a tool that they use to reason about phenomena like this: Homo economicus. This is an idealized model of human behavior, a hypothetical creature (/caricature) who makes perfectly “rational” decisions, where “rational” is a well-defined game-theoretic concept meaning (roughly) self-interested and utility-maximizing. In other words, a Homo economicus — of which no actual instances exist, but which every real human being approximates to a greater or lesser extent — will always, to the best of its available knowledge, make the decisions which maximize expected outcomes according to its own preferences.

If we (consumers) are swayed by emotional inception, then it seems we’re violating this model of economic rationality. Specifically, H. economicus has fixed preferences or fixed goals — in technical jargon, a fixed “utility function.” These are exogenous, unalterable by anyone — not the actor him- or herself and especially not third parties. But if inception actually works on us, then in fact our preferences and goals aren’t just malleable, but easily malleable. All an advertiser needs to do is show a pretty face next to Product X, and suddenly we’re filled with desire for it.

This is an exaggeration of course. More realistically, we need to see an ad multiple times before it eventually starts to rewrite our desires. But the point still stands: external agents can, without our permission, alter the contents of our minds and send us scampering off in service of goals that are not ours.

I know it’s popular these days to underscore just how biased and irrational we are, as human creatures — and, to be fair, our minds are full of quirks. [5] But in this case, the inception theory of advertising does the human mind a disservice. It portrays us as far less rational than we actually are. We may not conform to a model of perfect economic behavior, but neither are we puppets at the mercy of every Tom, Dick, and Harry with a billboard. We aren’t that easily manipulated.

Ads, I will argue, don’t work by emotional inception.

Truth in advertising

Well then: how do they work?

Emotional inception is one (proposed) mechanism, but in fact there are many such mechanisms. And they’re not mutually exclusive: a typical ad will employ a few different techniques at once — most of which are far more straightforward and above-board than emotional inception. Insofar as we respond to these other mechanisms, we’re acting fully in accordance with the Homo economicus model of human behavior.

The guiding principle here is that these mechanisms impart legitimate, valuable information. Let’s take a look at a few of them.

First, a lot of ads work simply by raising awareness. These ads are essentially telling customers, “FYI, product X exists. Here’s how it works. It’s available if you need it.” Liquid Draino, for example, is a product that thrives on simple awareness, because drains don’t clog all that frequently, and if you don’t know what Liquid Draino is and what it does, you won’t think to use it. But this mechanism is pervasive. Almost every ad works, at least in part, by informing or reminding customers about a product. And if it makes a memorable impression, even better.

Occasionally an ad will attempt overt persuasion, i.e., making an argument. It’s naive to think that this is the most common or most powerful mechanism, but it does make an occasional appearance: “4/5 doctors prefer Camels” or “Verizon: America’s largest 4G LTE network” and the like. Older ads were especially fond of this technique, but it seems to have fallen out of fashion when advertising hit its modern stride. [6]

Perhaps the most important mechanism used by ads (across the ages) is making promises. These promises can be explicit, in the form of a guarantee or warrantee, but are more often implicit, in the form of a brand image. When a company like Disney makes a name for itself as a purveyor of “family-friendly entertainment,” customers come to rely on Disney to provide exactly that. If Disney were ever to violate this trust — by putting too much violence in its movies, for instance — consumers would get angry and (at the margin) buy fewer of Disney’s products. So however the promise is conveyed, explicitly or implicitly, the result is that the brand becomes incentivized to fulfill it, and consumers respond (rationally) by buying more of the product, relative to brands that don’t put themselves “out there” with similar promises.

There’s one more honest ad mechanism to discuss. This one is termed (appropriately) honest signaling, and it’s an instance of Marshall McLuhan’s famous dictum, “The medium is the message.” Here an ad conveys valuable information simply by existing — or more specifically, by existing in a very expensive location. A company that takes out a huge billboard in the middle of Times Square is announcing (subtextually), “We’re willing to spend a lot of money on this product. We’re committed to it. We’re putting money where our mouths are.”

Knowing (or sensing) how much money a company has thrown down for an ad campaign helps consumers distinguish between big, stable companies and smaller, struggling ones, or between products with a lot of internal support (from their parent companies) and products without such support. And this, in turn, gives the consumer confidence that the product is likely to be around for a while and to be well-supported. This is critical for complex products like software, electronics, and cars, which require ongoing support and maintenance, as well as for anything that requires a big ecosystem (e.g. Xbox). The same way an engagement ring is an honest token of a man’s commitment to his future spouse, an expensive ad campaign is an honest token of a company’s commitment to its product line. [7]

So far so good. All of these ad mechanisms work by imparting valuable information. But as we’re well aware, not every ad is so straightforward and above-board.

Underhanded advertising

Consider this one for Corona:

Whatever’s going on here, it’s not about awareness, persuasion, promises, or honest signaling. In fact this image is almost completely devoid of information in the most literal sense. As Steven Pinker defines it, information is “a correlation between two things that is produced by a lawful process (as opposed to coming about by sheer chance).” [8] In this case, the image is so arbitrary that it can’t be conveying any information about Corona per se, as distinct from any other beer. Corona wasn’t specifically designed for the beach, nor does ‘beach-worthiness’ emerge from any distinguishing features of Corona. You could swap in a Budweiser or Heineken and no “information” would be lost. [9]

So instead of conveying information, this ad looks like a textbook case of emotional inception, i.e., creating an arbitrary, Pavlovian association between Corona and the idea of relaxation. The goal, presumably, is to seed us (viewers, consumers) with good memories, so that later, when shuffling down the beer aisle and spotting the Corona box, we’ll get the inexplicable warm fuzzies, and then: purchase!

Except I don’t think that’s what’s happening here. I don’t think this Corona ad — or any of the thousands of others just like it — is attempting to get away with inception. Something else is going on; some other mechanism is at play.

Let’s call this alternate mechanism cultural imprinting, for reasons that I hope will become clear. It’s closely related to, but importantly distinct from, emotional inception. And my thesis today is that the effect of cultural imprinting is far larger than the effect of emotional inception (if such a thing even exists at all).

Cultural imprinting is the mechanism whereby an ad, rather than trying to change our minds individually, instead changes the landscape of cultural meanings — which in turn changes how we are perceived by others when we use a product. Whether you drink Corona or Heineken or Budweiser “says” something about you. But you aren’t in control of that message; it just sits there, out in the world, having been imprinted on the broader culture by an ad campaign. It’s then up to you to decide whether you want to align yourself with it. Do you want to be seen as a “chill” person? Then bring Corona to a party. Or maybe “chill” doesn’t work for you, based on your individual social niche — and if so, your winning (E[xpected] V[alue]-maximizing) move is to look for some other beer. But that’s ok, because a successful ad campaign doesn’t need to work on everybody. It just needs to work on net — by turning “Product X” into a more winning option, for a broader demographic, than it was before the campaign.

Of course cultural imprinting works better for some products than others. What a product “says” about you is only important insofar as other people will notice your use of it — i.e., if there’s social or cultural signaling involved. But the class of products for which this is the case is surprisingly large. Beer, soft drinks, gum, every kind of food (think backyard barbecues). Restaurants, coffee shops, airlines. Cars, computers, clothing. Music, movies, and TV shows (think about the watercooler at work). Even household products send cultural signals, insofar as they’ll be noticed when you invite friends over to your home. Any product enjoyed or discussed in the presence of your peers is ripe for cultural imprinting.

For each of these products, an ad campaign seeds everyone with a basic image or message. Then it simply steps back and waits — not for its emotional message to take root and grow within your brain, but rather for your social instincts to take over, and for you to decide to use the product (or not) based on whether you’re comfortable with the kind of cultural signals its brand image allows you to send.

In this way, cultural imprinting relies on the principle of common knowledge. For a fact to be common knowledge among a group, it’s not enough for everyone to know it. Everyone must also know that everyone else knows it — and know that they know that they know it… and so on. [10]

So for an ad to work by cultural imprinting, it’s not enough for it to be seen by a single person, or even by many people individually. It has to be broadcast publicly, in front of a large audience. I have to see the ad, but I also have to know (or suspect) that most of my friends have seen the ad too. Thus we will expect to find imprinting ads on billboards, bus stops, subways, stadiums, and any other public location, and also in popular magazines and TV shows — in other words, in broadcast media. But we would not expect to find cultural-imprinting ads on flyers, door tags, or direct mail. Similarly, internet search ads and banner ads are inimical to cultural imprinting because the internet is so fragmented. Everyone lives in his or her own little online bubble. When I see a Google search ad, I have no idea whether the rest of my peers have seen that ad or not.

In a way, cultural imprinting is a form of inception, but it’s much shallower than the conventional (Pavlovian) account would have us believe. An ad doesn’t need to incept itself all the way into anyone’s deep emotional brain; it merely needs to suggest that it might have incepted itself into other people’s brains — and then (barring any contrary evidence about what people actually believe) it will slowly work its way into consensus reality, [11] to become part of the cultural landscape.

Unlike inception proper (which I don’t think actually exists), cultural imprinting is fully compatible with the Homo economicus model of human decision-making. It leaves our goals fully intact (typically: wanting the respect of our peers), and by imprinting itself on the external cultural landscape, merely changes the optimal means of pursuing those goals. The result is the same — we buy more of the products being advertised — but the pathways of influence are different.

To summarize:

Cultural imprinting = shallow emotional inception + common knowledge → inception into consensus reality

Ad examples

Let’s look at a few concrete examples. Here’s a Nike ad:

The emotional inception story goes like this: The above ad creates an association between the Nike brand and the idea of athletic excellence. Over time and with enough exposure, the customer will internalize this association. And because he personally values athletic excellence, he’ll begin to feel favorably disposed to the Nike brand and products. Later, when the customer is shoe-shopping, these positive associations and emotions will, at the margin, tip him toward buying a Nike shoe.

The cultural imprinting story goes like this: The above ad creates an association between the Nike brand and the idea of athletic excellence. (So far, so similar.) Over time and with enough exposure, the customer will realize that “Nike” is synonymous with “athletic excellence” out in the broader culture. Later, when he’s shopping for shoes, his brain will use this information (intuitively) to predict what his peers will think of him if he shows up on the court wearing Nike shoes (vs. wearing some other brand). At the margin, this will tip him toward buying Nike.

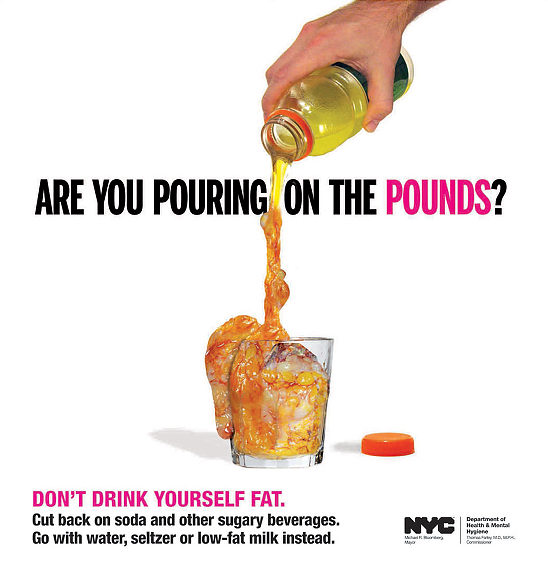

Here’s another ad, a kind of public-service health message:

At first blush, this ad seems to be making an individual appeal, a kind of argument: if you drink sugary beverages, you’re going to get fat. It seem to be the kind of ad that a person could experience privately (e.g. while browsing the internet) without diluting its effect, which would certainly be the case if it were working by persuasion or inception. But consider how much more effective this ad is when it’s displayed prominently in a public place — like on the subway (which is where it actually ran). Once everyone has seen the ad, it becomes common knowledge that sugary drinks are bad for you (and kind of disgusting), and you’ll start to worry what your friends might think if they catch you drinking one. Peer pressure is an extremely powerful force, and if advertising can tap into it even a fraction of that power, it can have a sizable effect.

Conspicuity

The key differentiating factor between the two mechanisms (inception and imprinting) is how conspicuous the ad needs to be. Insofar as an ad works by inception, its effect takes place entirely between the ad and an individual viewer; the ad doesn’t need to be conspicuous at all. On the other hand, for an ad to work by cultural imprinting, it needs to be placed in a conspicuous location, where viewers will see it and know that others are seeing it too.

We’ve already discussed how imprinting ads work best in broadcast media, but even within a single medium we should expect to see audience-size effects.

For example, consider advertising during the Superbowl, which draws 100 million viewers, vs. advertising during 100 different TV shows, each with an audience of 1 million viewers. Same total viewership, but in the case of the Superbowl, it’s one giant audience (very self-aware of its size), while in the case of the 100 different shows, the audience is fragmented.

If an ad works primarily by making emotional associations, it shouldn’t matter how fragmented the audience is — all that should matter is the total number of impressions (inceptions) the ad is able to make. On the other hand, if an ad works primarily by cultural imprinting, then we would expect the giant Superbowl audience to be more valuable than the fragmented audience of the same size. Why? Because during the Superbowl, everyone knows that everyone else is watching, and so any brand image that’s conveyed during the Superbowl is almost guaranteed to take root in the broader culture, and therefore to be perceived “correctly” at a later date.

If a relatively new/unknown brand of beer advertises itself as an “unpretentious fun-times party beer” during the Superbowl, you can bring that beer to your friend’s barbecue later, confident that your intentions will be understood. Whereas if the same unknown brand advertised itself across 100 different TV shows, and you only saw one of them — on an obscure cooking show (say) — you’d have no idea whether your friends at the barbecue would have the same understanding of the brand image, and whether they would perceive your intentions correctly.

So if an ad works by inception, we should expect the value (to the advertiser) to scale linearly with the size of the audience. On the other hand, if an ad works by cultural imprinting, we should expect its value (to the advertiser) to scale more than linearly with the size of the audience.

Which is true? I don’t know. But I suspect — confounding factors notwithstanding — that we see a more-than-linear relationship between audience size and ad value, which might account for some of the network effects enjoyed by big national (and international) brands.

Product types

If brand advertising works by emotional inception, we would expect brands to advertise themselves roughly in proportion to the size of the market for their products. On the other hand, if branding works by cultural imprinting, we should expect brands to advertise themselves in proportion both to the market size and to the conspicuousness of product usage.

Bed sheets are the perfect example. If ads work by emotional inception, why not seed us with the idea that Brand X bed sheets are the smoothest, softest, best-night’s-sleep bed sheets money can buy? On the other hand, if ads work by cultural imprinting, then we should expect almost no branded advertising for bed sheets, because their consumption is almost perfectly obscure (the opposite of conspicuous). It’s unlikely that any of your peers will ever see or feel your bed sheets, nor even inquire about them. Bed sheets just aren’t a social product, so cultural imprinting can’t work to convince us to buy them.

Q: Have you ever seen an ad for bed sheets? Can you even name a brand of bed sheet? If ads work by emotional inception, wouldn’t you expect to have seen at least a few ads trying to incept you with the idea that Brand X bed sheets are going to brighten your day? [12]

Here’s another market where brand advertising is conspicuously absent: gas stations. Let’s compare gasoline to soft drinks. Both are more-or-less commodity products. Yes, there are some minor variations in quality, but for the most part, one cola or gasoline is as good as the next. Both are product categories that the average American spends a lot of money on — probably in the $hundreds for soda and in the $thousands for gas. And yet we find brand advertising far more frequently in the soda market than in the gas market. Coke, Pepsi, Sprite, 7-Up, Dr. Pepper — these brands advertise themselves everywhere, creating identities for themselves that have almost nothing to do with their underlying products. Somehow Coke “convinces” us that drinking it will bring us happiness. But why don’t we see the same type of arbitrary associations crafted around gas station brands? If Coke can use advertising to charge a few more pennies per bottle — and finds it overwhelmingly in its interest to do so — why don’t Mobile, Citgo, Exxon, Valero, Shell, or Texaco do the same? If ads work by emotional inception, it seems these gas stations would benefit enormously by trying to seed us (consumers) with positive vibes, so that when we’re at an intersection with three different stations, we’re more likely to choose the advertised brand. The answer, I think, is that going to a gas station is a personal rather than a social activity, whereas drinking a soda is so often done in the company of others.

Admittedly Chevron does attempt, in the US, to carve out a brand image for itself, but the brand is largely based on a promise of quality rather than an arbitrary emotional or lifestyle association. The argument I’m making is that, if inception actually works, then we would expect to see a lot more of it in the (rather large) market for gas stations.

Why aren’t brands two-faced?

The inception model predicts that brands would benefit from being “two-faced” or “many-faced” — i.e., that brands ought to advertise to each audience separately, using whatever message is most likely to resonate with each particular audience, in order to provide maximum emotional impact.

So Corona, for example, could advertise itself to stressed-out dads as a relaxing, beach-vibes beer (like it does now). Meanwhile, it could advertise itself to college students as a fun-loving party beer, and to car-racing enthusiasts as the beer of champions. On NPR it might pose as distinctive or intellectual. Of course this immediately strikes us as wrong, somehow. But why? Beers advertise themselves in all sorts of ways. There are very few intrinsic qualities to a given product (like Corona) that forces it to stick with one brand image. So why do brands limit themselves to one central message?

Gatorade is another brand that could flit between various positive associations, or hedge its bets with multiple associations at once, as long as the emotions didn’t interfere with each other. In fact, layering associations on top of each other could conceivably produce an even greater effect, more than the sum of the individual associations. One ad might link Gatorade to athletic performance, while another might link it to “having fun,” while yet another might play up its taste. Why not? All of these are time-honored branding strategies. Who doesn’t like to have fun or drink something that tastes great? Plus, we all already associate Gatorade with sports — why not give us another reason to buy it? It’s like making multiple emotional “arguments” for the same product.

But clearly this is not what happens. Instead, brands carve out a relatively narrow slice of brand-identity space and occupy it for decades. And the cultural imprinting model explains why. Brands need to be relatively stable and put on a consistent “face” because they’re used by consumers to send social messages, and if the brand makes too many different associations, (1) it dilutes the message that any one person might want to send, and (2) it makes people uncomfortable about associating themselves with a brand that jumps all over the place, firing different brand messages like a loose cannon.

If I’m going to bring Corona to a party or backyard barbecue, I need to feel confident that the message I intend to send (based on my own understanding of Corona’s cultural image) is the message that will be received. Maybe I’m comfortable associating myself with a beach-vibes beer. But if I’m worried that everyone else has been watching different ads (“Corona: a beer for Christians”), then I’ll be a lot more skittish about my purchase.

Brands build trust over time, and not just trust in the quality of their product, but trust that they won’t change their brand messaging too sharply or too quickly.

Absence of personal advertising

If ads work by inception, then we should be able to advertise to ourselves just as effectively as companies advertise to us, and we could use this to fix all those defects in our characters that we find so frustrating. If I decide I want to be more outgoing, I could just print a personalized ad for myself with the slogan “Be more social” imposed next to a supermodel or private jet, or whatever image of success or happiness I think would motivate me the most. And I would expect such an ad, staring me in the face every day, to have a substantial “inception-style” effect on my psyche. I would gradually come to associate “being social” with warm feelings, and eventually — without ever lifting a finger — I would find myself positively excited about the prospect of going out to bars and parties. Effortless self-improvement: isn’t that the magic bullet solution we’re always seeking?

But there is no magic bullet, because these arbitrary-association ads don’t work by inception. They work by cultural imprinting, and when the intended audience is a single person, there’s no “culture” on which to imprint — no one else to appreciate the intended messages.

The blog Take Back Your Brain advocates “personal marketing,” i.e., advertising to oneself. [13] Affirmations and motivational posters seem to be after a similar effect. But if inception is as effective as advertising commentators make it out to be, I’d expect to see a lot more personal marketing than we actually observe.

No immunity

A final thought.

The problem with the inception model is that it fuels a hope that we could be immune to ads, if only we were diligent enough or if we developed the right kind of mental fortitude. If only we had a stronger psychological “immune system,” ads wouldn’t be able to get in — even by the emotional backchannel.

You can see such hope glimmering whenever someone admonishes you to “think critically” about advertising. The Lifehacker article I mentioned earlier, for example, offers two tactics for countering the effects of unwanted ads: (1) Don’t Forget to Think, and (2) Be Wary of Your Emotional Responses. The article admits that we may never develop full immunity, but with enough care and practice, it suggests, we can at least learn to mitigate some of the more pernicious effects.

But if I’m right about how ads actually work, then this advice is useless. Ads get us to buy things not in spite of our rationality, but because of it. Ads target us not as Homo sapiens, full of idiosyncratic quirks, but as utility-maximizing Homo economicus.

When ads work by conveying honest information, of course, we’re happy to consume such ads (and the products they’re marketing), because the ads are doing us a valuable service. But when an ad works by cultural imprinting, we feel we’re being manipulated somehow. And we are. Before seeing the ad, the product wasn’t worth very much to us, but after seeing the ad, we find ourselves wanting to buy it (and at a premium, no less). The problem is that there’s no escape, no immunity, from this kind of ad. Once we see it — and know that all our peers have seen it too — it’s in our rational self-interest to buy the advertised product.

Avoiding ads doesn’t help much either. Because brand images are part of the cultural landscape we inhabit, when we block ads or fast-forward through them, we’re missing out on valuable cultural information, alienating ourselves from the zeitgeist. This puts us in danger of becoming outdated, unfashionable, and otherwise socially hapless. We become like the kid who wears his dad’s suit to his first middle-school dance.

Of course, haplessness isn’t so bad for some people in some cultural niches, and I count myself extremely lucky to live among such a crowd. But if most of your peers are exposed to these ads, you’re missing out by not watching them too.

[1] Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. [web]

[2] Christopher Nolans’s Inception (2010). [web]

[3] Nigel Hollis, “Why Good Advertising Works (Even When You Think It Doesn’t)” (31 August 2011), The Atlantic. [web]

[4] Adam Dachis, “How Advertising Manipulates Your Choices and Spending Habits (and What to Do About It)” (25 July 2011), Lifehacker. [web]

[5] Much of the research underpinning this belief was undermined by the reproducibility crisis in scientific research about human behaviour, which occurred after this article’s publication. See, for example, on the scientific fraud committed by acclaimed academic Dan Ariely, “The Fall of a Superstar Psychologist” (2023). [web] — R. D.

[6] Image search for “old ads.” [web]

[7] Skeptical about “honest.” — R. D.

[8] Despite the innocuousness of this definition, readers should know Steven Pinker is a very questionable reference point in general. [web] — R. D.

[9] As Greg Rader and Caroline Zelonka have pointed out, the association between Corona and the beach isn’t wholly arbitrary. Corona is a Mexican beer, originally consumed (by American tourists) primarily in beach towns — so, as Greg puts it, there is at least a “circumstantial” basis for the association. Even for other products, the emotional or lifestyle associations probably have some anchor in reality.

[10] “Common Knowledge (logic)” on Wikipedia. [web]

[11] “Consensus reality” on Wikipedia. [web]

[12] Caroline and Alex Hawkins point out that bed sheets are sometimes advertised, in a way that smacks of inception. See e.g. the ads for Wamsutta sheets. [web] I’d still suggest that the scarcity of bed-sheet ads (relative to, e.g., soda ads) is largely due to the asocial nature of the product, but it seems there are exceptions.

[13] Lynn, “The REALLY personal ads” (12 November 2006), Take Back Your Brain! [web]