Credit to Anton P. for his original translation. [1]

Contents

- I. The Origins of Romanticism

- II. Elements of Romanticism in 18th Century European Literature and the First Cycle of Romanticism: The French Revolution

- III. The Second Cycle of Romanticism: The Second Round of Bourgeois Revolutions

- IV. Romanticism in Russia

- V. The Fall and the Afterlife of Romanticism

- VI. The Style of Romanticism

- VII. Romanticism in Soviet Literature

I. The Origins of Romanticism

The term Romanticism designates a complex synthesis of literary and general cultural movements that developed from the end of the 18th century to the middle of the 19th. Though it tends to be more associated with either end of these movements, it refers to very diverse phenomena. In the most limited and concrete sense, Romanticism refers to the ideological movement that arose after a turning point in the development of the French Revolution, from the Terror to Thermidor, as a result of the dissatisfaction that the revolution had generated among certain sections of the bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie. But the word itself was in use even earlier, in the era that led up to the revolution. Its meaning, then, incorporates elements from certain pre-revolutionary trends, which only upon modification result in post-revolutionary Romanticism.

The genre that took its name from the French word for the novel, roman, in the 16th-18th centuries, was a genre that retained many features of medieval knightly poetics and held very little regard for the rules of Classicism. A characteristic feature of the genre was fantasy: dreamy imagery, disregard for plausibility, idealization of heroes and heroines in the spirit of conventional chivalry, action set in an uncertain past or in distant lands, a predilection for the mysterious and magical. To designate the features characteristic of this genre, adjectives emerged — “romanesque” in French and “romantic” in English. In 18th-century England, in connection with the awakening of the bourgeois personality and heightened interest in the “life of the heart,” the word began to acquire new content, attaching to itself the aspects of the novel-form which most resonated with the new bourgeois consciousness, such as those stylistic elements that classical aesthetics rejected, but which nevertheless now began to be deemed artful regardless. “Romantic,” then, denoted that which, above all, despite not adhering to the formal harmony of Classicism, “touched the heart” and “created a mood.”

The taste for the “romantic” developed in close connection with the growing cult of the “natural” as opposed to the “artificial” — with “feeling” as opposed to “reason.” Bourgeois literary critics have as of late dubbed a number of elements expressing these attitudes “pre-Romantic.” These phenomena are inseparable from the omnipotent subjectivism (“sentimentalism”) that swept through European literature in the decades before the French Revolution, accompanying the growth of bourgeois-democratic aspirations (Rousseau and others). In light of all this, the term Romanticism was easily extended, by many later authors, to the entire bourgeois-democratic movement, which rebelled simultaneously against feudalism and against the reformist rationalism of the bourgeois enlighteners.

Belinsky’s definition, for example, identifies the concept with all pre-revolutionary subjectivism: “Romanticism is nothing but the inner world of the human soul, the hidden life of its heart.” The discovery of this “inner world” and “hidden life” furnishes the content of the pre-revolutionary literature of the 18th century — from the first English pre-Romantic writers to the German Stürmers, to Goethe and Schiller. All later ramifications of Romanticism are in one way or another determined by this discovery. Instead of the harmonic stylization of Classicism, which seeks to highlight the abstract-logical essence of what is depicted, “romantic” poetics put forward the concept of “picturesque” — a term that became widespread in the 18th century in the sense of “a characteristic specific to painting in contrast to sculpture.” In painting, “romantic” aesthetics were especially championed by Rembrandt, whose sharp opposition of light to shadow served not to reveal a rationally abstract idea, but to create an emotionally charged image. When we consider more vulgar literature, objects associated with Romantic aesthetics serve as “expressive” components — castles, dungeons, caves, the moon in the clouds, and so on. At a higher level, the same tendency leads to increased “chiaroscuro” [2] in the depiction of passions. This prose can easily degenerate into mere rhetoric, but it can also achieve stunning eloquence. The resulting new imagery serves not merely as ornamentation, but in fact communicates more strongly and effectively the emotions depicted. The pioneers of this new imagery were Rousseau (especially in his prose poems — “Rêveries d’un promeneur solitaire,” 1777-1778) and the young Goethe, whose early poem “Willkommen und Abschied” [1770-1771] can be considered the birth of the new European lyric poetry.

From the 1770s onwards, Germany became the main source of new trends. The underdevelopment of the German economy, which excluded the possibility of direct revolutionary action, gave the liberation movement of the German burghers a purely “ideal” character. The German revolution takes place only in consciousness, without seeking or hoping to move into political action. There is a large gap between the dream and its realization. This gives rise to the most characteristic feature of all late Romanticism: the contrast between “ideal” and “reality.”

For half a century the whole of German culture develops in accordance to this rupture which characterizes the politically powerless German bourgeoisie. At the same time, however, it reveals exceptional creative energy when it comes to the various fields of artistic expression. In this period of greatest political insignificance, Germany revolutionizes European philosophy, European music, and European literature. In this last field a powerful movement reaches its peak under the name of “Sturm und Drang” — it takes the conquests of the English and Rousseau and raises them to their highest level, making a final break with Classicism and bourgeois-aristocratic Enlightenment, and inaugurating a new era in the history of European literature. The innovation of the Stürmers is not merely formal, or innovation for its own sake. Their varied experiments are all in search of forms suitable for a new, rich content. Deepening, sharpening, and systematizing everything newly introduced by pre-Romanticism and Rousseau; taking its first successful steps into early bourgeois realism (for example, Schiller’s completion of “bourgeois drama” originating in England); German literature embraces and masters a huge literary heritage from the Renaissance (primarily Shakespeare) and folk poetry, approaching antiquity in a new way. So, against Classic literature, a partly new and partly revived literature steps forth, one that is richer and more appealing to the budding consciousness of the growing bourgeoisie.

The German literary movement of the 1760s-80s decisively influenced the conception of Romanticism more broadly. While in Germany Romanticism was opposed to the “classical” art of Lessing, Goethe, and Schiller, outside Germany all German literature, starting with Klopstock and Lessing, is perceived as innovative, anti-Classical, and “romantic.” Against the backdrop of the dominance of Classical canons, Romanticism is perceived as purely adversarial, as a movement that throws off the oppression of the old authorities regardless of its positive content. It is in this sense of anti-Classical innovation that the term Romanticism comes to be primarily understood in France and especially in Russia, where Pushkin aptly christens it “Parnassian atheism.”

II. Elements of Romanticism in 18th Century European Literature and the First Cycle of Romanticism: The French Revolution

The “romantic” features of European literature as a whole are by their very nature not hostile to the general line of the bourgeois revolution. Unprecedented focus on the “innermost life of the heart” reflected one of the most important aspects of the cultural revolution that accompanied the political revolution underway: the birth of a personality free from feudal ties and religious authority, which was made possible by the development of bourgeois relations. But in the development of the bourgeois revolution (in the broad sense), the self-assertion of the individual inevitably came into conflict with the real course of history. Of the two processes of “emancipation” that Marx speaks about, the subjective emancipation of the individual reflected only one — the political (and ideological) emancipation from feudalism. The other — the economic “emancipation” of the small proprietor from the means of production — was perceived by the emancipating bourgeois personality as alien and hostile. This hostility to the industrial revolution and to the capitalist economy is first of all evident in England, where it finds a very vivid expression in the first English Romantic, William Blake. In the future it becomes characteristic of the romanticization of literature as a whole, and goes far beyond these limits. But this attitude towards capitalism can by no means be regarded as necessarily anti-bourgeois. Though it is characteristic of the ruined petty bourgeoisie and of the destabilized nobility, it is also very common among the bourgeoisie itself. “All good bourgeois,” Marx wrote (in a letter to Annenkov), “desire the impossible, i.e., the conditions of bourgeois life without the inevitable consequences of these conditions.” The “romantic” rejection of capitalism can exhibit the most diverse class character — from petty-bourgeois economically reactionary yet politically radical utopianism (Cobbet, Sismondi), [3] to noble reaction, to a purely “Platonic” rejection which accepts capitalist reality as an unaesthetic but useful world of “prose,” which must be supplemented by a “poetry” which stands aloof from its brutality. Naturally, such a Romanticism flourished especially in England, where its main representatives were Walter Scott (in his poems) and Thomas Moore. The most popular form of Romantic writing is the horror novel. But along with these essentially philistine forms of Romanticism, the contradiction between the inner soul and the ugly “prosaic” reality of “an age hostile to art and poetry” finds a much more significant expression in, for example, the early (before exile) poetry of Byron.

The second contradiction from which Romanticism is born is the contradiction between the dreams of a liberated bourgeois personality and the realities of the class struggle. Initially, the “hidden life of the heart” appears in close unity with the struggle for the political liberation of the class. We find such a unity in Rousseau. But soon enough the first develops in inverse proportion to the realities of the second. [4] The late emergence of Romanticism in France is owed to the fact that the French bourgeoisie and bourgeois democracy, during the Revolution and under Napoleon, had too many opportunities for practical action, and thus did not experience then the “inner-world hypertrophy” that leads to Romanticism. The fright the bourgeoisie experienced at hands of the revolutionary dictatorship of the masses [1773-4] did not have romantic consequences because it did not last long, and the outcome of the revolution turned out to be in its favor. After the fall of the Jacobins, the petty bourgeoisie also remained realistic, since its social program was largely fulfilled, and during the subsequent Napoleonic era it was able to divert its revolutionary energy towards its own interests. [5] Therefore, until the restoration of the Bourbons, we find in France only the reactionary Romanticism of the noble emigrés (Chateaubriand), or the anti-national Romanticism of certain bourgeois groups opposed to Empire and making common cause with foreign intervention (Madame de Staël).

Meanwhile, in Germany and in England personality and revolution did come into conflict. The contradiction was twofold: on the one hand, between the dream of a cultural revolution and the impossibility of a political revolution (in Germany due to the underdevelopment of the economy, in England due of the protracted realization of the purely economic tasks of the bourgeois revolution and the impotence of democracy before the ruling bourgeois-aristocratic bloc); on the other hand, the contradiction between the dream of a revolution and its real appearance. The German burgher and the English democrat were frightened by two aspects of the French revolution — the revolutionary activity of the masses, so formidably manifested in 1789-1794, and the “anti-national” character of the revolution, such that it was perceived as a form of French conquest. These reasons logically, though not immediately, lead the German opposition burghers and English bourgeois democracy to form a “patriotic” bloc with their ruling classes. The moment when the “pre-Romantic” German and English intelligentsia denounce the French Revolution as “terrorist” and a national threat can be considered the birth of Romanticism in the more limited sense of the word. This process unfolded most characteristically in Germany. [6] The German literary movement, which was the first to christen itself with the name Romanticism (first in 1798) and thus had a great influence on the fate of the term, however, did not itself have much influence on other European countries (with the exception of Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands). Foreign attention on Germany was primarily focused on pre-Romantic German literature, especially Goethe and Schiller. Goethe — a forefather of European Romanticism, the greatest poet of the “hidden life of the heart” (Werther, early lyrics), the creator of new forms of verse, and finally a poet-thinker who opened the way for fiction to master the most daring and diverse philosophical themes — Goethe is certainly not a romantic in this specific sense. He’s a realist. But like all German culture of his time, Goethe stands under the sign of the wretchedness of German reality. His realism is detached from the real practice of his national class, he reluctantly remains “on Olympus.” Therefore, stylistically, his realism is clothed in by no means realistic clothes, and this outwardly brings him closer to the Romantics. But Goethe is completely alien to the protest against the course of history that so characterizes the Romantics, just as he is alien to utopianism and a departure from reality.

The relationship between Romanticism and Schiller is different. Schiller and the German Romantics were sworn enemies, but from a European perspective Schiller must undoubtedly be recognized as a Romantic. Politically, renouncing revolutionary dreams even before the revolution, Schiller became a banal bourgeois reformist. But this sober practice was combined in him with a completely Romantic utopianism focused on the creation of a new ennobled humanity, disregarding the course of history, re-educating it through beauty. In Schiller the voluntaristic “good will” arising from the contradiction between the “ideal” of the liberated bourgeois personality and the “reality” of the era of bourgeois revolution, which takes its desires as predictions, was particularly pronounced. “Schillerian” motifs play an enormous role in all later liberal and democratic Romanticism, starting with Shelley.

The three stages that German Romanticism went through can be observed in other European literatures of the era of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, remembering, however, that they are dialectical stages, and not chronological subdivisions. In the first stage, Romanticism is still a definite democratic movement and retains a politically radical character, but its revolutionary spirit is already purely abstract — it is repelled by the concrete forms of revolution, by the Jacobin dictatorship, and by popular revolution in general. Its most vivid expression is found in Germany, in the system of Fichte’s subjective idealism, which is nothing other than the philosophy of an “ideal” democratic revolution, one that occurrs only in the head of the bourgeois-democratic idealist. Parallel phenomena occur in England, in the work of William Blake, especially his “Songs of Experience” (1794) and “Marriage of Heaven and Hell” (1790), as well as in the early works of future “Lake” poets — Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey.

In the second stage, finally disappointed by real revolution, Romanticism seeks ways to realize its ideals outside of politics, and finds an outlet primarily in the activity of free creative imagination. The notion of the artist as a creator, spontaneously producing a new reality out of his fantasy, which played a huge role in bourgeois aesthetics, emerges. This stage, representing the maximum sharpening of the specificity of Romanticism, was again especially pronounced in Germany. As the first stage is associated with Fichte, so the second stage is associated with Schelling, to whom the philosophical development of the idea of the artist-creator belongs. [7] In England, this stage, without presenting the philosophical richness that we find in Germany, represents the flight from reality into the realm of free fantasy in a much more naked form.

With frankly fantastic and arbitrary “creativity,” the Romanticism of the second stage seeks its ideal in another world, which appears to itself as objectively in existence. From the purely emotional experience of intimate communion with “nature” — which plays a huge role already in Rousseau — arises a metaphysically realized Romantic pantheism. With the later transition of the Romantics to reaction, this pantheism tends to compromise and then to submit to church orthodoxy. But at first, for example in the poems of Wordsworth [1798-1805], it is still sharply opposed to Christianity, and even in the next generation it is assimilated by the democratic Romantic Shelley without significant changes, under the characteristic name of “atheism.” In parallel to pantheism, Romantic mysticism develops, which at this stage still retains sharply anti-Christian features (Blake’s “prophetic books”).

The third stage is Romanticism’s final transition to a reactionary position. Disillusioned by real revolution, weighed down by the fantasy and fruitlessness of its lonely “creativity,” the Romantic seeks support in super-personal forces — nationality and religion. Translated into the language of real relations, this means that the burghers, represented by their democratic intelligentsia, join the national bloc with the ruling classes, accepting their hegemony, but bringing them a new, modernized ideology, in which loyalty to the king and the church is justified on grounds not of authority and fear, but on the sentimental needs and the dictates of the heart. Finally, at this stage, Romanticism becomes its own opposite: it rejects individualism and completely submits to feudal power, but this is superficially embellished by romantic phraseology. In literary terms, this self-denial of Romanticism is the canonized Romanticism of La Motte-Fouquet, Uhland, etc. In political terms, “Romantic politics,” which raged in Germany after 1815.

At this stage, the old genetic link between Romanticism and the feudal Middle Ages acquires new significance. The Middle Ages, as the age of chivalry and Catholicism, become an essential component of the reactionary-Romantic ideal. They are reinterpreted as an age of free obedience to God and lord (Hegel’s “heroism of submission”).

The medieval world of chivalry and Catholicism is also the world of autonomous guilds; its culture is much more “popular” than later monarchical and bourgeois culture. This opens up great opportunities for Romantic demagoguery, for that “democratism of the past,” which consists in substituting the interests of the nation for the current (or dying out) views of the people.

It is at this stage that Romanticism does a lot for the revival and study of folklore, especially folk songs. And it must be admitted that, despite its reactionary goals, Romanticism’s work in this area is of significant and lasting value. Romanticism did much to study the true life of the masses, repressed under the yoke of feudalism and early capitalism.

The real connection of Romanticism at this stage with the feudal-Christian Middle Ages was strongly reflected in the bourgeois theory of Romanticism. The concept of Romanticism as a Christian and medieval style, in contrast to the “classics” of the ancient world, emerges. This view found its fullest expression in Hegel’s aesthetics, but it was widespread in much less philosophically complete forms. Awareness of the deep opposition between the “romantic” worldview of the Middle Ages and the Romantic subjectivism of contemporary times led Belinsky to the theory of two Romanticisms: “the Romanticism of the Middle Ages” — romanticism of voluntary submission and resignation, and “modern Romanticism” — progressive and liberating.

III. The Second Cycle of Romanticism: The Second Round of Bourgeois Revolutions

The first cycle of Romanticism generated by the French Revolution results in Reactionary Romanticism. With the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the beginning of the upsurge that sets the stage for the second round of bourgeois revolutions, a new cycle of Romanticism begins, and it is significantly different from the first. This difference is primarily a consequence of the different nature of the revolutionary movement. The French Revolution of 1789-1793 is replaced by many “small” revolutions, which either end in compromise (the revolutionary crisis in England 1815-1832); or take place without the participation of the masses (Belgium, Spain, Naples); or where the people, appearing only for a short period of time, gracefully give way to the bourgeoisie immediately after victory (the July Revolution in France). At the same time, no country claims to be an international fighter for revolution, as France did. These circumstances contribute to the disappearance of the fear of revolution, whereas the frenzied revelry of reaction after 1815 strengthens the oppositional mood. The ugliness and vulgarity of the bourgeois system are revealed with unprecedented clarity, and the first awakening of the proletariat, which has not yet embarked on the path of revolutionary struggle (even Chartism observes bourgeois legality), arouses sympathy in bourgeois democracy for the “largest and poorest classes.” All of this makes the Romanticism of this era essentially liberal-democratic.

A new type of romantic politics emerges — liberal-bourgeois, whose ringing phrases stir in the masses faith in the imminent realization of a (rather vague) ideal, thus dissuading them from revolutionary action. This ideal is utopian in petty-bourgeois fashion: a dream of a realm of freedom and justice without capitalism, but retaining private property (Lamennais, Carlyle).

Although the Romanticism of 1815-1848 (outside Germany) is painted in predominantly liberal-democratic colors, it can in no way be equated to liberalism or to democracy. The essential aspect of Romanticism remains the discord between ideal and reality. Romanticism continues to either reject or voluntaristically “transform” reality. This allows Romanticism to serve as a means of expression for the purely reactionary noble yearning for the past and the defeatism of the nobility (Vigny). In the Romanticism of 1815-1848 it is not as easy to identify stages as in the previous period, especially since Romanticism is now spreading to countries that are at very different stages of historical development (Spain, Norway, Poland, Russia, Georgia). It is much easier to identify instead three main currents within Romanticism, each represented by one of the three great English poets of the post-Napoleonic decade: Byron, Shelley, and Keats.

Byronic Romanticism is the most vivid expression of the self-affirmation of the bourgeois personality, which began in the era of Rousseau. Strongly anti-feudal and anti-Christian, it is at the same time anti-bourgeois, in the sense of denying the positive content of bourgeois culture in its entirety, in contrast to its more complex anti-feudal negation. Byron was in the end convinced that there was a complete gap between the bourgeois ideal of liberation and bourgeois reality. His poetry is the self-affirmation of personality, but cursed by the consciousness of the futility of this self-affirmation. Byron’s “universal heartbreak” easily becomes an expression of the most diverse forms of individualism, but it does not find an outlet—because it is rooted in a defeated class (Vigny), or because it is surrounded by an environment too immature for action (Lermontov, Baratashvili).

Shelley’s Romanticism is a voluntaristic affirmation of the utopian ways of transforming reality. This Romanticism is organically linked to democracy. But Shelley is anti-revolutionary, because he puts “eternal values” above the needs of the struggle (rejection of violence), and regards political “revolution” (without violence) as a key detail in the cosmic process that must give rise to a “golden age” (“Prometheus Unchained” and the final chorus of “Hellas”). The main representative of this type of Romanticism, with great individual differences from Shelley, was the “Last of the Mohicans of Romanticism,” old man Victor Hugo, who carried the Romantic banner to the eve of the age of imperialism.

Finally, Keats can be regarded as the founder of a purely aesthetic Romanticism which sets itself the task of creating a world of beauty, towards which one can escape from the ugly and vulgar reality. In Keats himself this aestheticism is closely connected with Schiller’s dream of the aesthetic re-education of mankind and the realization of a future world of beauty. But rather than being driven by a dashed expectation, he exhibits a purely practical concern for the creation of a concrete world of beauty here and now. From Keats come the English aesthetes of the second half of the 19th century, who can no longer be classified as Romantic, because they are already completely satisfied with what really exists. Essentially the same aestheticism emerges even earlier in France, where Mérimée and Gautier soon go from “Parnassian atheists” and participants in Romantic battles, to purely bourgeois, politically indifferent aesthetes (i.e., philistically conservative), free from any Romantic anxiety.

The second quarter of the 19th century witnesses the widest spread of Romanticism in the various countries of Europe (and America). In England, which produced three of the greatest poets of the “Second Cycle,” Romanticism did not form a school, and began to retreat early when faced with the forces characteristic of the next stage of capitalism. In Germany, the struggle against reaction was also, to a large extent, a struggle against Romanticism. The greatest revolutionary poet of the era — Heine — emerged from the Romantic tradition, and a Romantic “soul” lived in him to the end, but unlike Byron, Shelley, or Hugo, in Heine the left-wing politician and the Romantic did not merge, but struggled.

Romanticism flourished most magnificently in France, where it was especially complex and contradictory, uniting representatives of very different class interests under the same literary banner. In French Romanticism it is particularly clear how Romanticism could be an expression of the most diverse divergence from reality — from the impotent longing for the past of a nobleman — albeit one that absorbed all bourgeois subjectivism (Vigny), to a voluntaristic optimism that replaces a genuine understanding of reality with more or less sincere illusions (Lamartine, Hugo), to the purely commercial production of “poetry” and “beauty” for the bourgeois bored by the world of capitalist “prose” (Dumas Sr.).

In countries suffering from national oppression, Romanticism is closely associated with the national liberation movements, but mainly with the periods of their defeat and impotence. Here, too, Romanticism is an expression of very diverse social forces. Thus, Georgian Romanticism (Baratashvili, Orbeliani) is associated with the nationalist nobility, a completely feudal class that nevertheless, in its struggle against Russian tsarism, avails itself of the ideology of the bourgeoisie. National-revolutionary Romanticism was especially developed in Poland. If on the eve of the November Revolution [1830] Mickiewicz’s “Konrad Wallenrod” achieves a truly revolutionary accent, then after its defeat his Romantic essence blossoms with particular eloquence, in the contradiction between the dream of national liberation and the inability of the progressive gentry to unleash the peasant revolution. In general, it can be said that in nationally oppressed countries the Romanticism of revolutionary groups is inversely proportional to their genuine democracy and their organic connection with the peasantry. The greatest poet of the national revolutions of 1848, Petőfi, is completely alien to Romanticism.

IV. Romanticism in Russia

Russian Romanticism did not introduce fundamentally new aspects into the general history of Romanticism, as it was derivative of its Western European counterpart. The most authentic Russian Romantics come after the defeat of the Decembrists [1825]. The collapse of hopes, the oppressive reality of Nicholas I’s rule, creates the most suitable environment for the development of romantic moods, as it aggravates the contradiction between ideal and reality. We thus observe almost the entire spectrum of shades of Romanticism — apolitical, metaphysically and aesthetically closed, but not yet reactionary Schellengism; the “Romantic politics” of the Slavophiles; the historical Romanticism of Lazhechnikov, Zagoskin, etc.; the socially-colored Romantic protest of the advanced bourgeoisie (N. Polevoy); the withdrawal into fantasy and “free” creativity (Veltman, some works of Gogol); and finally, the Romantic rebellion of Lermontov, who was strongly influenced by Byron, but also echoed the German Stürmers. However, even in this, the most Romantic period of Russian literature, Romanticism is not the lead tendency. The essential approach of Pushkin and Gogol stands outside Romanticism, and lays down the foundations for realism. The decline of Romanticism occurs almost simultaneously in Russia and in the West. [8]

V. The Fall and the Afterlife of Romanticism

From the 1830s onwards, the struggle against Romanticism is grounded in new realistic positions, which oppose the denial and voluntaristic distortion of reality in favor of knowing reality as it is. Realism as a literary movement is preceded by a number of phenomena that mark the ideological liquidation of the Romantic period — Hegel’s dialectics, the realistic historicism of French historians (fundamentally opposed to the reactionary German historicism, which “glorified the whip simply because it was a historical whip”), the enormous successes of the natural sciences. With the capitalist economy firmly established, cadres of intellectuals grow interested in adapting to capitalism rather than fighting against it. Meanwhile, radical democracy fights against Romanticism.

By the time of the 1848 Revolution, Romanticism as a trend had largely been liquidated, although some Romantic motifs continue to feature in European literature even today (symbolism, expressionism, etc.).

In Russia, where the tasks of the bourgeois revolution remained unresolved until the Socialist Revolution of 1917, there remained grounds for various manifestations of Romanticism (elements of Romanticism in Dostoevsky, the Symbolists). Russian bourgeois literature of the 1905-1917 epoch exhibits a lively stylistic connection with Romanticism, which also reflects a kinship of content. Blok’s creativity unfolds under the sign of a contradiction, between the hatred the “prodigal son” feels against bourgeois reality and his fear of proletarian revolution, resulting in a hopeless search for an otherwordly ideal (The Beautiful Lady), or in the voluntaristic distortion of reality (the image of “Russia”, the image of Christ in The Twelve).

Romanticism, organically linked to the illusions and disappointments of petty-bourgeois democracy, proved to be more tenacious. In this respect, the work of the early Romain Rolland, who later came to a realistic appraisal of the proletarian revolution, is characteristic. [9] Various petty-bourgeois Romantics appeared in Russia during the October Revolution. In accepting the revolution, but accepting it not for what it really was, the Russian petty-bourgeois intelligentsia had to undergo a long period of contradictory dreams and realities. Some of these Romantics, those associated with kulak “democracy,” became hostile to the proletarian revolution (Klyuyev), and others became bogged down in hopeless longing for an unrealized bourgeois-peasant kingdom (Yesenin). The better part, having first accepted October as a successful populist revolution, after many twists and turns managed to finally understand its true nature, and began to develop the proletarian outlook that would lead to Socialist Realism (Bagritsky and others).

VI. The Style of Romanticism

It is not possible to characterize the style of Romanticism in general. It is possible, however, to establish how it distinguishes itself from the Classicism that preceded it and from the bourgeois Realism that came to replace it (and partly from the preceding Realism of the middle of the 18th century), as well as to identify some of its characteristic tendencies, although none of them span the entire Romantic movement and some are mutually exclusive. Romanticism rejects both sides of Classicism — its subordination to conventional tradition (feudal-monarchical authority) and its rationalism. Classicism aspires to a canonical impersonal beauty, Romanticism seeks out the free expression of the individual. Classicism builds its images rationally and logically, simplifying and generalizing as much as possible, highlighting their logical essence. Meanwhile, Romanticism in a broad sense strives not towards slender elegance, but rather towards maximum emotional impact.

More specifically Romantic is the “expressionist” technique — making a thematic choice purely on the basis of emotional impact, appealing to imagination and disregarding substance. This is developed and refined in the “horror” genre. An early example of such “arousal of emotion” can be seen in Bürger’s famous “Lenore.” To the same family belong “Queen of Spades” and many of Mérimée’s stories. This kind of “Romanticism” blossomed brightly in the Soviet literature of the NEP period, nourished to a large extent by the contrast between the recent Civil War and Soviet “everyday life” (Babel, partly Tikhonov).

Much more specifically Romantic is the tendency towards variations of disembodied imagery, which arises directly from the desire to create a world alien to reality. It is expressed either in sensual attributes abstracted away from their objects, or by emphasizing such elements of reality that are most dissimilar to ordinary, rigid material bodies — clouds, waves, shimmering light, etc. This tendency is closely related to the musicalization of the word, the focus on its sonic aspects instead of its semantic content. [10] This tendency, already strong in German Romantic lyrics (where it is partly negated due to the rootedness of its folk orientation), reaches its extreme expression in Shelley — the fourth act of “Prometheus Unchained” is a veritable orgy of verbal music and disembodied imagery.

Along with the rich and varied musical orchestration of the Shelley type, Romanticism, at certain stages of its development, develops the simple folk love song. This, of course, is connected to Romanticism’s democratic roots, but the specifically Romantic song flourishes particularly during Romanticism’s reactionary third phase (primarily in Germany), in connection with demagogic “popular” nationalism. At the same time, the appropriation of folk songs by the Romantics is very one-sided: they favor motifs of longing, resignation, passivity, or idyllic conciliation. This is even more true of the Romantic fairy tale, which is idyllically conciliatory through-and-through.

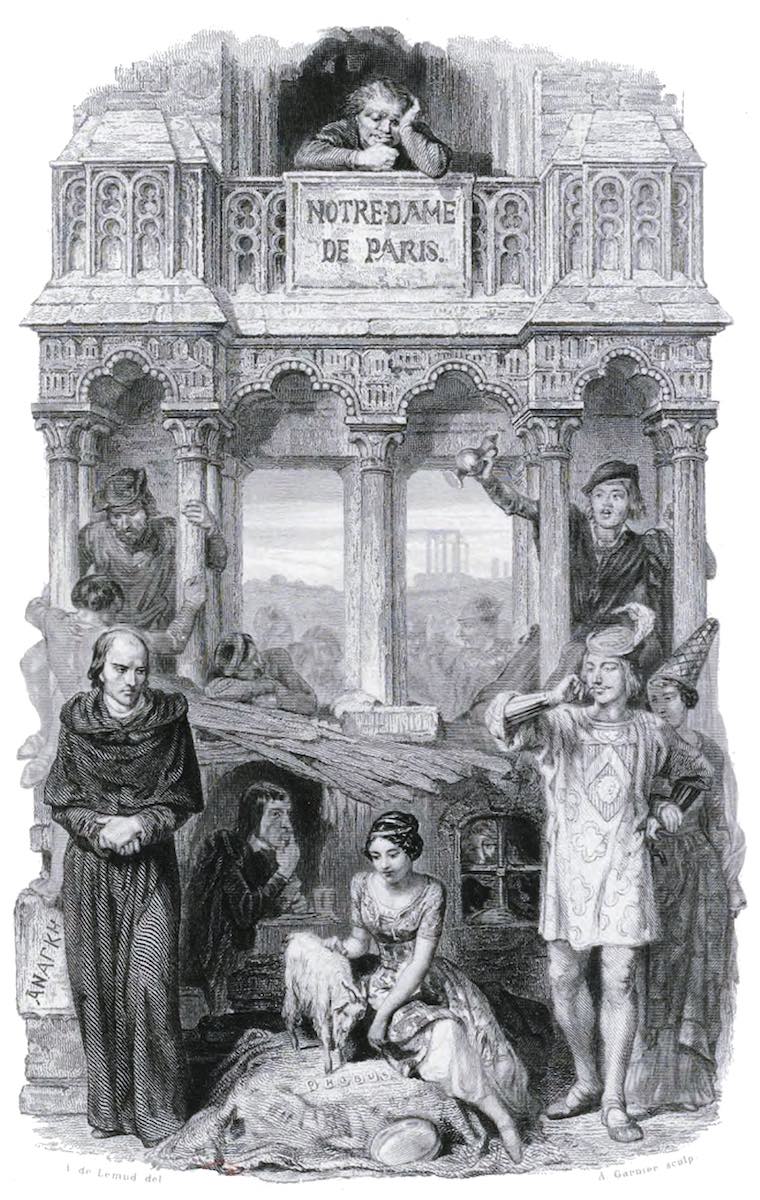

Another specifically Romantic tendency, directly related to the basic opposition of the ideal to reality, is the tendency to contrast the low, ugly, or comic reality to the ideal dream. The entirety of Hoffman’s poetics is based on a wide-ranging deployment of this technique, but we also include here such a characteristically Romantic figure as Quasimodo in Hugo’s “Hunchback of Notre Dame.”

Along with the tendency towards “musicalization,” towards “contrast,” and towards expressive imagery, Romanticism is also characterized by the opposite tendency: the direct and loud expression of feelings in words. This characteristic, naturally associated with the emotional self-affirmation of the individual, goes back to the earliest phases of pre-Romanticism (Jung’s Nights, 1742), and it does not leave Romanticism until the very end. Degenerating at times into the worst kind of rhetoric, at others Romanticism achieved magnificent eloquence on this score, creating a weapon that could well be used in political poetry (Hugo, Lermontov).

Romanticism presents itself as an art of imagination and expression that finds itself in opposition to Realism, an art of cognition. In reality, Romanticism, like any art, is a form of cognitive activity. But it alienates itself from a conscious approach to the cognition of reality: it sees its task as either the “expression” of the personality of the poet or the “creation” a world, thus escaping reality or complementing reality. It should be noted that, for all its proclaimed anti-Realism, Romanticism was never a stranger to the most daring use of real-life images for its purposes. However, the Romantics subordinated their real-life images, either to a contrasting depiction of the contradiction of dream and reality (Hoffmann) or to expressionistic expression (Mathurin, Jeanin), and were not in the least concerned with the cognition of concrete social reality.

Another feature of Romanticism, against which Realism fought, was the idealization of heroes and heroines, and the inflation of feelings to hyperbolic proportions. Here Romanticism was essentially conventional, merely the last heir to a long tradition which could be traced back to the chivalric novel and the “high” genres of Classicism. However, in Romanticism the idealization of heroes is associated with the general conception of the ideal and with the voluntaristic transformation of reality, as well as with the poetics of contrasts.

From our point of view, bourgeois Realism has an incomparably greater cognitive and artistic value than Romanticism. However, bourgeois Realism has downsides: firstly, its tendency towards an objectivist, non-evaluative (i.e. essentially slavishly subordinate) attitude to reality, and, secondly, its tendency towards a flattening, a “prosaicization” of reality, a denial of heroics, etc. [11] Romanticism is, at least in some of its currents, free from both of these tendencies. Romantic style is intensely emotional and judgemental. But it should be remembered that this judgement is purely Romantic, since it remains essentially verbal and abstract. Romanticism’s love of heroism and the richness of life is not exclusively Romantic, but recalls the most ancient aspirations of human art, aspirations which only the bourgeoisie could kill. The legacy of Romanticism thus cannot be rejected. In the first place, because at the heart of Romanticism lies a passionate (though distorted) protest against capitalism, against “an age hostile to poetry and art”, against a system hostile to all the best manifestations of the human personality, against a system whose elimination is our triumph. Romanticism affirmed the human personality, although in conditions that precluded the possibility of its true affirmation. It rebelled against objective bourgeois reality, although it opposed it only with subjective bourgeois consciousness. But in our era, when the real liberation and affirmation of the individual is underway, not in spite of but as a result of the creation of a new socialist reality, the past dead ends and tragedies of Romanticism have considerable instructive value.

Secondly, Romanticism was a tremendous manifestation of creative energy directed toward art. The great artists of Romanticism greatly enriched our means of artistic expression. They did a great deal, especially for lyricism, deepening and confirming the stylistic revolution initiated by Goethe. Critical mastery of Romanticism’s achievements is an integral part of the general struggle for its literary heritage. Even if the theory underlying Romantic poetry and art were to be rejected, we cannot but recognize that the field of critique of Romanticism produced extraordinary achievements. It could even be said that criticism in the modern sense of the term only became a widespread practice in the wake of Romanticism. Finally, we must not forget the greatest merits of Romanticism in the fields of literary history, folklore, etc. — up to and including linguistics.

VII. Romanticism in Soviet Literature

Our era raises the question of “Soviet Romanticism” — of whether we need Romance. In answering this question, we must first of all avoid terminological confusion. If by “Romanticism” we understand Romanticism in the exact historical sense, as a phenomenon which unfolded between the Great French Revolution and the first revolutionary movement of the proletariat, then it must be said that there is no such proletarian (socialist) Romanticism, and that there cannot be. The proletariat’s struggle against class oppression takes the form neither of an ideal dream nor of a voluntarist pursuit of illusions. It’s a concrete struggle for a different reality, powered by the very logic of capitalism, yet realized only in the practice of the communist revolution. The outlook of the proletariat one of “practical materialism,” and thus excludes all kinds of Romanticism.

If we were to speak of revolutionary Romanticism, we could consider Gorky’s early [pre-1900] works. There are undoubtedly Romantic elements in them — fantastic images, a tendency to idealization. However, Gorky’s heroic Romanticism substitutes the illusions of the petty-bourgeois for the vigorous confidence of the proletariat, which, although not yet risen as a mass to a scientific-communist understanding of revolution, already spontaneously senses its potential.

Revolutionary Romanticism in this exact sense of the word is alive and well in the revolutionary literature of capitalist countries, where it reflects the participation of the petty-bourgeois masses in the revolutionary movement, and the persistence of petty-bourgeois sentiments among the proletariat. Such Romanticism is characteristic of other proletarian writers from the intelligentsia, politically linked to the proletariat but not yet so organically attuned to its worldview, so that their artistic approach to reality is not yet expressed in a suitably realistic form. In Soviet literature, poetry of petty-bourgeois vintage has not been eliminated either. Recently, it has expressed voluntarism, because the question of the society of the future coexists with the realities of the current stage of the struggle for socialism. Such Romanticism cannot be regarded as a hostile phenomenon. One can speak of this Romanticism as a desirable and necessary element of Soviet literature, which looks to the future, so long as the word “Romanticism” is given a meaning clearly distinguished from the historical phenomenon called Romanticism.

This understanding of the word “Romance” has recently become quite firmly established in Soviet criticism. Romanticism in this sense includes a number of features that distinguish the art of socialism, which is Realistic in nature, from bourgeois Realism. A love of heroics, albeit of heroics that are not fantastic; heroics which have become not only a reality, but a mass reality. This — love for the vibrancy and richness of real life and real nature — is an inseparable manifestation of the emancipation and development of the socialist individual, before whom the bourgeois-Romantic awakening of the indiviual is like a candle before the sun. Finally, there is a purely stylistic aspect: forms of expression with aims other than capturing the outwards apperance of reality. Unlike bourgeois Realism, Socialist Realism does not consider outwards appearance an integral feature. In some writers, these features appear in such a stable configuration and so definitely color their work that we can in this sense speak of a Soviet, Socialist Romantic style, as a specific and full-fledged variant of Socialist Realism. A striking example of this kind of work would be “Riders” by Yanovsky.

[1] Anton P.’s translation of “Romanticism” at the Marxists Internet Archive. [web]

[2] Chiaroscuro — Italian for “light-dark”; bold contrasts between light and shadow. — R. D.

[3] Lenin treats Sismondi at some length in The Sentimental Criticism of Capitalism, (1897). [web] — R. D.

[4] Romanticism becomes the reaction of a middle class pressured both from above — by industrial capitalism — and from below — by revolutionary plebeian elements.

[5] Bonapartist “class peace” and French expansionism effectively keep the interests of the petty bourgeoisie safe from the pressures of large-scale industrial capitalism.

[6] See German Literature, section “The Epoch of Industrial Capitalism,” where it is exhaustively covered. [web]

[7] Losurdo provides a brief and interesting discussion of the contrast between Schelling’s passions and Hegel’s reason in his interview with Gargani. [web] — R. D.

[8] For more on Russian Romanticism, see Russian Literature. [web]

[9] Romain Rolland is the author of a very famous communist motto popularized by Antonio Gramsci: “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” [web] — R. D.

[10] César Vallejo also discusses an analogous aspect of bourgeois literature in “Duel Between Two Literatures” (1931). [web] — R. D.