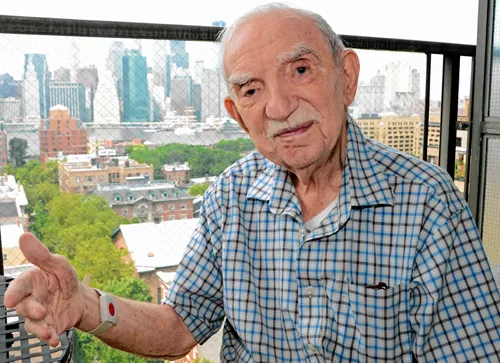

Harry Kelber, 90 years old at the time he wrote this piece, was a lifelong member of the American Trades Union movement. Starting as a teenager in 1933, he “fell out of step” with its mainstream when, in the McCarthyite 1950s, he opposed the “purge of communism in its own ranks.” Ever since, he remained something of a relentless insider-outsider. He wrote exposés of well-connected corrupt figures, attempted to run as an alternative in leadership contests, and poured his efforts into mass education. I only know of him through various obituraries that I was able to find online, written after his death in 2013, which might be useful for curious readers. [1] [2]

This piece is composed of various articles originally published at Harry Kelber’s The Labor Educator website, in weekly installments, over the November-December 2004 period. It serves as a summary of various works documenting the sinister role that “free and independent” American unions have historically played in capitalism’s world-wide war against Communism. No changes have been made other than compiling the articles together into one large one, adding a table of contents and a few illustrations, and tracking down likely sources for all the quotations.

— R. D.

Contents

- 1. Meany Hired a Former Top Communist To Run AFL-CIO’s International Affairs

- 1.1. Failed to Oust Leftists in United Auto Workers

- 1.2. Inducements for Foreign Union Activists

- 1.3. AFL’s Splitting Tactics in Italy

- 1.4. AFL and CIO Disagree on Rebuilding German Unions

- 2. AFL is Funded for Covert Activity by CIA in Long-standing Ties with Spy Agency

- 3. U.S. Labor Secretly Intervened in Europe, Funded to Fight Pro-Communist Unions

- 3.1. Brown Used Bribery to Split French Labor

- 3.2. How AFL Undermined a New World Labor Federation

- 3.3. Differing Views About Brown’s Legacy

- 4. U.S. Labor Reps. Conspired to Overthrow Elected Governments in Latin America

- 4.1. AFL’s Romauldi Was Long-Time CIA Agent

- 4.2. AIFLD Linked to Big Business and Military in Latin America

- 5. Kirkland Built A Secret Global Empire With U.S. Funds to Control Foreign Labor

- 5.1. The Endowment Replaces CIA as Grant Dispenser

- 5.2. Kirkland Applauds Victory of Polish Shipyard Workers

- 5.3. Funding Dual Unions in Russia

- 5.4. Teachers Union Conducts Campaign to “Educate” Russians

- 6. Do Solidarity Center’s Covert Operations Help American Labor on Global Problems?

- 6.1. Is Solidarity Center Continuing Kirkland’s Game Plan?

- 6.2. Is Solidarity Center an Arm of the State Department?

- Conclusion

1. Meany Hired a Former Top Communist To Run AFL-CIO’s International Affairs

For nearly 30 years, George Meany, a New York Irish Catholic plumber, who rose to be the undisputed leader of the American labor movement, collaborated with Jay Lovestone, a Lithuanian-born Jew, who was secretary general of the American Communist Party from 1927 to 1929, until he was expelled in a losing confrontation with Russia’s Joseph Stalin.

It was an odd partnership. Meany, the portly, cigar-chomping, strong willed labor leader, who was on first-name terms with every U.S. president from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan, and Lovestone, a crafty, single-minded, behind-the-scenes operator, who had hands-on experience about what was going on, not only in the Soviet Union, but also Western Europe.

What brought the two together was a shared hatred of Communism and an ambitious plan to build a global network of pro-democratic unions under their control. They were introduced by David Dubinsky, president of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers in October 1941, shortly after Meany became secretary-treasurer of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Dubinsky, Lovestone’s benefactor, told Meany: “The son of a bitch is okay, he’s been converted.” [3]

Meany, who had a vision of establishing ties with labor federations throughout the world with the nerve center at AFL headquarters in Washington, hired Lovestone to develop his international affairs program. It was a bold, unorthodox appointment, but the few labor leaders who knew about it did not raise objections.

Lovestone, a New York City College graduate, became a Communist in 1917 at age 17, and rose to head the U.S. party, but was expelled in 1929 on Stalin’s orders at a Comintern meeting in Moscow, after demanding some independence for American communists. He then spent the next dozen years in an unsuccessful effort to form an opposition communist party.

At age 41, Lovestone found a new mission: to eliminate communists from the American labor movement. He set his sights on the CIO, where communists and “fellow travelers” were in the leadership or exercised growing influence in some 18 international unions, and he singled out the United Auto Workers, the second largest in the CIO, as his target.

Lovestone had gained a foothold in the union movement through his friendship with Sasha Zimmerman, manager of ILGWU’s Local 22. He soon came to the attention of Dubinsky, a hard-bitten anti-communist, who gave him a sizable slush fund to purge the UAW of leftist leaders. For two years, Lovestone served as chief of staff to UAW’s first president, Homer Martin, arranging for the discharge of known leftists and replacing them with trusted “Lovestonites” from New York.

1.1. Failed to Oust Leftists in United Auto Workers

At the UAW convention in Milwaukee in August 1937, Lovestone hoped to get rid of two leftist vice presidents and the treasurer, but he was foiled by John L. Lewis, who addressed the convention and urged a united leadership. Lewis had a working relationship with communists, who were among his best organizers and who held their jobs “at his pleasure.”

Lovestone’s meddling into UAW affairs and his attempted coup earned him the bitter enmity of Walter Reuther, later to become the union’s president, who regarded him as a disrupter and spoiler. [4]

Nevertheless, Lovestone, backed by Meany, became more influential within the labor movement. At the AFL’s 1944 convention, the Free Trade Union Committee (FTUC) was created to assist free trade unions abroad, particularly in Europe. Lovestone was named its secretary.

With the end of World War II, there began intense rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union to win the allegiance of Greece, Turkey, Italy, West Germany and France. In these struggles, the U.S. State Department found a willing ally in the FTUC and began to supply it with substantial funds and contacts.

By 1946, the State Department had twenty-two labor attachés stationed in embassies around the world. Lovestone, using Meany’s political leverage with President Truman, managed to get appointments for AFL candidates, who subsequently would report not only to the State Department, but to him personally. He also formed alliances with senior officers in the State Department who shared his anti-Soviet convictions and who furnished him with intelligence reports.

In constant communication with his network of agents in an increasing number of countries, Lovestone was able to operate in secret from an office in the ILGWU headquarters in New York City with a few assistants, receiving reports and issuing directives, masterminding political events on a worldwide chessboard. He would make progress reports to Meany, Dubinsky and a third AFL officer, Matthew Woll, president of the Photoengravers Union. Not a word of what Lovestone was doing ever reached union members.

With lavish government funding, Lovestone was able to offer enticing bribes to foreign union leaders to do his bidding. He could have them order national demonstrations and paralyzing strikes against any government that did not support American foreign policy. The FTUC was able to encourage and subsidize dual, competing unions in countries where mainstream unions were considered pro-communist. The FTUC became, in effect, an arm of the State Department, enabling it to meddle in the internal affairs of foreign countries through their labor movements.

Lovestone’s grand mission, fully supported by Meany, Dubinsky and Woll, was to eliminate pro-communist unions everywhere, especially in countries under Soviet domination, and supplant them with “free” unions, American style, that respected the rules of a free market economy.

1.2. Inducements for Foreign Union Activists

Trade unionists from foreign countries were invited to spend as many as three months to study the American economy and democratic political system and compare them with Soviet models. They met with union leaders in various cities. They learned how U.S. unions function and what features they could apply to their own labor movements. Lovestone was on the lookout for people whom he could manipulate in future actions in their respective countries.

When they returned home, many indoctrinated foreign union leaders continued to receive a stipend from the FTUC. Foreign unions favored by Lovestone received printing presses, office equipment and subsidies for educational programs. Every effort was made to cultivate their loyalty to the FTUC in the event of any future controversy involving American economic and political interests.

Lovestone was committed to aggressive intervention abroad and plunged into the battleground for union dominance in France, Italy and West Germany. At an FTUC meeting in January 1946, Lovestone endorsed a plan to give Irving Brown, his long-time associate, the sum of one hundred thousand dollars to build an anti-communist bloc of delegates to disrupt the forthcoming convention of the left-wing CGT, France’s largest union. For Lovestone, “France is the number one country in Europe from the point of view of saving the Western labor movement from totalitarian control.” [5]

Brown’s strenuous efforts to disrupt the CGT convention failed. The communists had a four-to-one majority and enacted decisions that solidified their control. But Brown was not deterred. In early 1947, the FTUC sent $50,000 to Paris to help in the formation of a dual union, the Force Ouvrière, as a breakaway from the CGT. The new union was founded in December 1947 by 250 delegates at a national conference in Paris.

On January 7, U.S. Ambassador Jefferson Caffery, who had been working closely with Brown, cabled Robert Lovett, then acting Secretary of State, that the Force Ouvrière’s split with the CGT was “potentially the most important political event since the liberation of France.” [6]

1.3. AFL’s Splitting Tactics in Italy

Lovestone and Brown used the same technique that had been so successful in France: to split off a rival union from the dominant communist federation, the CGIL. The CGIL was the umbrella for Italian workers representing the three main political parties (Communist, Socialist and Christian Democrat). The AFL strategy was to shore up the anti-communist forces within the CGIL, with the aim of splitting them off into a separate union.

The State Department let it be known that the price of Marshall Plan aid to Italy was the removal of the communists from the government. To prevent the communists from winning the crucial April 1948 parliamentary elections, the Central Intelligence Agency, newly formed in 1947, sent $10 million for covert election campaigning. The Christian Democrats won, with 48% of the vote, a serious blow to the communists.

In June 1948, Lovestone and Dubinsky came to Rome to promote a split from the CGIL of the three non-communist groups: the Catholic Christian Democrats, the Centrist Republicans and the Socialists, with promises of ample funding if they broke away as a unit. Only, the Catholic Christian Democrats left to form the Free Italian Confederation of Labor (LCGIL). Promised financial aid by labor attaché Tom Lane. LCGIL’s president, Giulio Pastore said he would need $1.5 million in operating expenses for the first nine months, an amount readily approved by the State Department.

In 1949, the Republicans and Socialist unions left the CGIL to form their own federation, FIL. Finally, on May Day 1950, Lovestone and Brown had achieved their objective: the merger of the three anti-communists unions, to be known as the Italian Federation of Trade Unions (CISL).

1.4. AFL and CIO Disagree on Rebuilding German Unions

At the end of World War II, defeated Germany was divided into four zones of Allied occupation, with the Americans, British, French and Russians, each controlling one sector. A major question in the American zone was what steps should be taken to revive the German trade unions.

There was sharp disagreement between AFL and CIO strategists on how the German unions in the American zone should be restored and restructured. The CIO position, supported by the U.S. officer in charge of labor issues, Brig. Gen. Frank McSherry, was that the trade unions had to be reorganized at the “grass roots.” [7]

The plan called for the election of shop stewards in each plant every three-months. At the end of two years, there would be formal recognition of new unions, based on new leaders, rather than the unions that had existed in pre-Hitler days.

The AFL position, as expressed by Lovestone, was: “The FTUC is in favor of giving former German trade unionists an opportunity to resume their work in the trade union movement without any hindrance. We also favor the immediate return of the properties confiscated by Hitler to the trade unionists.” [8]

There was fierce infighting between partisans of each approach, with frequent appeals to Gen. Lucius Clay, the American occupation commander, by both sides. By October 1945, shop stewards had been elected in 3,000 plants in the American zone. But by November, the AFL was already working with pre-war labor leaders, whose unions were functioning, although unofficially.

The AFL trusted the pre-war German labor leaders because it had had friendly ties with them for many years before the start of the war. It feared that the “bottoms-up” approach would lead to a Soviet takeover of the German labor movement.

With AFL President George Meany using his influence with the White House, the State Department announced in March 1946 that “military government should permit proven anti-Nazis to organize primary trade unions.” [9]

One month later, a meeting of German labor leaders established thirteen unions. By October 1949, the West German Labor Federation (DGB) would hold its first convention, with 16 autonomous unions representing five million members.

Lovestone sent a confidential report on the achievements of the Free Trade Union Committee to Meany and Woll in November 1947 that said: “Our trade union programs have penetrated every country in Europe… The AFL has become a world force in the conflict with world Communism in every field affecting international labor.” [10]

Meanwhile, American unions and their members were kept in the dark about the AFL’s covert operations in Europe, and the huge government payoffs it was getting to disrupt and weaken left-wing labor federations.

At that moment, ironically, Republicans had launched an anti-communist campaign against unions here at home, with the 1947 passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, dubbed “the slave labor act” by CIO unions.

2. AFL is Funded for Covert Activity by CIA in Long-standing Ties with Spy Agency

On December 10, 1948, Matthew Woll, president of the photoengravers union and one of the four labor leaders on the AFL’s Free Trade Union Committee, wrote Frank Wisner, a top officer of the Central Intelligence Agency: “This is to introduce Jay Lovestone… He is duly authorized to cooperate with you in behalf of our organization and to arrange for close contact and reciprocal assistance in all matters.” [11]

Thus, the AFL began a relationship with the intelligence agency that was to endure for better than two decades. Wisner recognized that the FTUC could be an important intelligence-gathering asset and was willing to pay a substantial price for its assistance, said to have amounted to many millions of dollars over the years.

From Lovestone’s perspective, the additional funding would help him expand operations in China, Japan, India, Africa and the Arab countries. Although he chafed at having to make reports to Wisner, he needed the agency’s help. While he supplied the CIA with intelligence reports from his FTUC operatives, he also received information from Wisner, who advocated “support of anti-communists in free countries.” [12]

Lovestone had no trouble cooking the FTUC’s balance sheets from the prying eyes of any dissident. In 1949, for example, AFL-affiliated unions contributed $56,000 to the committee, but an additional $203,000 was attributed to “individuals,” actually the CIA. In 1950, the agency funneled another $202,000 to the FTUC; in later years, the agency’s funding to the AFL was kept secret, with the amount dependent on the size and nature of the covert operation.

Lovestone’s very extensive, and expensive, anti-communist operations in Europe were largely financed from money siphoned off from the Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Plan), which provided $13 billion to Western European nations between 1948 and 1950.

Under the Plan’s rules, each country receiving financial aid had to refund 5% of the total to U.S. occupation forces for administrative expenses. That turned out to be a slush fund (referred to as the “sugar fund”) of more than $800 million that the Free Trade Union Committee was allowed to draw from and spread lavishly to subvert a gallery of European labor leaders to support whatever American policy was demanded of them.

When Marshall Plan funds dried up, Lovestone became more dependent on CIA funding. But the CIA’s new director, Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, who had been Eisenhower’s chief of staff in Europe during World War II, was a tough administrator who started questioning the expenditures for the AFL’s clandestine operations.

To clarify the relationship, a “summit” meeting was held on November 24, 1950. In attendance for the AFL were Meany, Dubinsky, Woll and Lovestone. The CIA was represented by Smith, its director, and his top assistant, Frank Wisner.

There was general agreement that the collaboration had worked well and should continue. But Lovestone, while complimenting the CIA for the assistance it had given the AFL in several emergency situations, still insisted that improvements had to be made in the relationship. He had given the CIA a list of the funding he required for special projects, but it had been ignored. Smith said he would review the proposals.

When Smith brought up the idea of including the CIO into the agency’s operations, the AFL group quickly voiced their strong objections. They said the CIO was inexperienced in this kind of activity and was riddled with communists and other undesirable elements. Lovestone said that if the CIO were brought in, all their work would be placed in jeopardy. The CIO could not be trusted to maintain the secrecy that was required by both the AFL and CIA operations.

Meany said he was worried that the CIO would get some of its friends in the Truman administration to recommend that they share equally in funding and participation in international labor activity. (Just a few months earlier, the CIO had expelled eleven international unions with over one million members for “following the Communist Party line.”) Meany threatened to withdraw from the arrangement with the CIA if the CIO were brought into the partnership.

But to Smith and Wisner, it seemed absurd to work closely with one wing of the labor movement while totally ignoring the other. The best that the AFL guests could get out of them was that enlisting the cooperation of the CIO was not imminent.

The propriety of an American labor movement becoming the instrument or partner of a government intelligence agency was fully acceptable to the Meany-Dubinsky-Woll trio, as long as it was in the service of an anti-Soviet crusade and the defeat of communist-led unions. Nor did any U.S. union leader dare to challenge the clandestine, quid pro quo relationship between organized labor and the international spy agency.

It was Thomas Braden, an assistant to CIA director Allan Dulles, who became the contact man with the CIO. Walter Reuther, the UAW president, received $50,000 in cash from Braden, who flew to Detroit to deliver it.

There are no public records of how much money the CIA gave both branches of the labor movement. There was no congressional oversight of the agency. As Braden said: “The CIA could do exactly as it pleased. It could buy armies. It could buy bombs. It was one of the first world-wide multinationals.” [13]

Despite plenty of evidence to the contrary, Meany, Dubinsky and Woll insisted to their dying day that neither they nor Lovestone or the AFL were involved in any way with the CIA. It would have been an explosive scandal that would probably have destroyed them as labor leaders if it was found they had not only worked with the CIA but also had accepted funding from the intelligence agency to carry out its directives.

There is no evidence that CIA money ever reached AFL headquarters in Washington or that Meany got a penny of it, but that Lovestone operated as a CIA agent with Meany’s approval is beyond doubt.

Meany effectively used his anti-communist ideology after the merger of the AFL and CIO in 1955. By this time, most militant, left-wing leaders had been expelled from the CIO, so his task was considerably easier. In 1957, he persuaded the AFL-CIO Executive Council to approve an eyebrow-raising resolution, entitled “Racketeers, Crooks, Communists, and Fascists.” [14]

Lumping racketeers and crooks with communists was patently ridiculous. The complaint against communists never was that they were thieves and embezzlers, like a number of AFL-CIO leaders, but rather they were committed to a theory and practice of unionism that was at odds with Meany’s.

Linking fascists with communists was a disingenuous attempt to make the resolution palatable to union leaders. Meany never persecuted any fascists, nor even identified any in the labor movement. His target was not only communists, but also radicals and dissidents whose views he was intent on suppressing.

It is worth noting that the combined membership of the AFL and CIO at the time of the merger totaled 15,913,077. Today, 49 years later, the AFL-CIO has 13 million members, nearly three million fewer than it had in 1955.

Meany believed in “top-down” leadership. He had little regard for the rank-and-file, and boasted that he had never walked a picket line. He rarely appeared at rallies or marches in support of a labor issue. He preferred — and was a master at — making deals with people in high places that he thought would benefit working people. He did not consider himself accountable to union members. He resented criticism and saw to it that critics were either punished or disregarded.

In his 27 years as AFL-CIO president, there was not one woman on the 33-member Executive Council and, at most, only two African-American or Hispanic union leaders.

Meany was clearly a strong leader, but it is arguable whether he did more good than harm for the labor movement and the nation’s working people.

3. U.S. Labor Secretly Intervened in Europe, Funded to Fight Pro-Communist Unions

Shortly after the end of World War II, the AFL began conducting clandestine operations to disrupt existing pro-communist unions and institutions in France, Italy, Germany and Greece.

The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, recent allies in the war against Hitler Germany, was beginning to heat up. It was also to be fought between the labor movements of both superpowers, acting as surrogates of their respective countries.

The Free Trade Union Committee (FTUC) was established at the AFL’s 1944 convention with a mandate to assist unions abroad. It was tightly controlled by four prominent labor leaders: George Meany, then the federation’s secretary-treasurer; David Dubinsky, president of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union; Matthew Woll, president of the Photoengravers Union, and George Harrison, president of the Railway Clerks.

Their long-term mission was to build a world-wide organization of “free” trade unions under the domination of American labor. As they worked toward this goal, they knew they could count on the support of the U.S. government and the nation’s business community, normally hostile toward unions.

The FTUC was an “off budget, off contribution” agency, whose financial operations were kept secret, even from union leaders in the AFL’s upper echelons. Two of its first actions were to appoint Jay Lovestone as executive secretary and name Irving Brown as the AFL’s sole representative in Europe.

Brown, born in Bronx, N.Y. in 1911, was a stocky, five feet nine, undistinguished in appearance and unpretentious in public. He received a Bachelor’s Degree in Economics from New York University and spent several years as a union organizer in tough campaigns, including the Ford plant in South Chicago and the coal mines of Harlan County, Kentucky.

What made Brown an outstanding choice for the job was his sharp mind, inexhaustible energy, photographic memory for names of places and people, and his talent for making friends with important U.S. and foreign labor and government officials. His wife, Lillie, who spoke five European languages, served as his secretary and adviser.

Irving had a close, if not warm, relationship with Jay Lovestone, a former leading Communist, whom George Meany had handpicked to run the AFL’s International Affairs Committee. They made a perfect team, with Jay plotting the anti-communist labor strategy for Europe and Irving carrying it out, a partnership that lasted for more than two decades.

3.1. Brown Used Bribery to Split French Labor

Arriving in Paris in October 1945, Brown said of his duties as the AFL representative: “I want to build up the non-communist unions in France and Italy and weaken the CGT in France and the CGIL in Italy.” [15] He was to report regularly to Lovestone and Meany.

Irving preferred to make private deals with European labor leaders, where, as the AFL’s sole representative, he had a distinct advantage. But he could play hard ball, when necessary. In 1947-48, he hired squads of goons, many of them criminals, to wrest control of the docks at Marseilles and other southern ports from the communist port unions, thus enabling allied ships to deliver food, machinery and other items in short supply to France and Italy.

But Irving, as talented as he was, could not have cleared the docks for allied shipping or effectively challenged the communist-led unions without the huge sums of money which he continuously received to bribe foreign union leaders, organize demonstrations, call or break strikes, influence union elections and disrupt communist meetings.

Between 1945 and 1948, Brown was getting funds from the AFL treasury, the U.S. State Department and major corporations like Exxon, General Electric, Singer Sewing Machines and others that had commercial interests in Europe. Then, in 1948, the U.S. launched the Marshall Plan (European Recovery Plan), which allotted $13 billion to Western Europe, but nothing to countries in the Soviet orbit.

The Marshall Plan stipulated that 5% of the funds should be used for administrative purposes and rebuilding Western European unions. But since Irving had developed a cozy relationship with Averill Harriman, the Marshall Plan director, he was able to get a good slice of the $800 million available in the “sugar fund” to finance his expanding activities.

When the Marshall Plan folded in 1950, the Central Intelligence Agency, established in 1947, was there to continue funding Brown’s secret operations on an even grander scale. The CIA turned over tens of millions to the FTUC, because the spy agency found Brown’s covert operations useful. Neither the CIA nor the FTUC were obliged to report these undercover financial transactions.

3.2. How AFL Undermined a New World Labor Federation

In September 1945, delegates from the labor federations of 56 counties met in Paris to form the World Federation of Trade Unions. Among its affiliates were the CIO, the United Mine Workers, the U.S. railroad unions, the British Trade Union Congress and most of the functioning unions in Europe, Asia and Africa.

The one glaring exception was the American Federation of Labor. Meany, refusing to join the WFTU, said its affiliates lacked “the basic freedoms of speech, press, assembly and religion.” The WFTU, he said, was “primarily part of a struggle to secure world political power for the Communists in the postwar world.” [16]

The AFL began a strong campaign to undermine the WFTU and establish a rival world labor federation under its influence, if not direct control. Brown used his anti-communist contacts within the WFTU to sharpen divisions over the Marshall Plan and NATO, with the pro-Soviet unions refusing to endorse both. The crisis over the Berlin Blockade and Russian expansionist moves in Czechoslovakia also helped Brown to cause defections within the WFTU.

By December 1949, delegates from organized labor in 53 countries, including the British Trades Union Congress and the CIO, met in London to form the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU). Meany had achieved his dream, but not without the CIA lurking in the background and providing the funds and covert assistance.

But the fledgling ICFTU wasn’t the compliant vehicle that Meany had expected to promote his ambitions. Many of its members came from countries that were hostile to each other: Arabs and Israelis, Greeks and Turks, Indians and Pakistanis. There were tensions between unions representing the industrially-developed countries and those from Third World countries. Others had developed ties with communist unions in Eastern Europe that American labor leaders frowned upon. And most began to resent the domineering attitude of the U.S. labor delegation.

Frustrated by what he called the “stodgy bureaucracy” of the ICFTU staff in Brussels, Brown, with Meany’s approval, began moving aggressively on projects involving union development in Asia, Africa and Latin America. This further infuriated the ICFTU leadership who, depending on consensus, rarely acted decisively.

For nearly two decades, the uneasy, fragile relationship between the AFL and the ICFTU held on until 1969, when Meany, over the objections of Lovestone and Brown, pulled out of the world labor organization, saying he felt “completely frustrated with the operations of the ICFTU and no longer saw amy justification to remain within it.” [17]

What also angered Meany was the growing trend within ICFTU affiliates to establish working relations with unions in Eastern Europe, especially the Soviet Union, through exchanges of worker delegations, joint meetings and actions of international solidarity.

The ICFTU received ample funding from the Central Intelligence Agency, channeled to it via both the AFL and CIO in 1950 and thereafter, according to John Ranelagh, a top authority about the CIA. Ranelagh says the CIA’s support in the early 1950s also “was given to West German labor unions through the good offices of Walter Reuther, head of the United Auto Workers Union, and his brother Victor, a resident of West Germany. [18]

Philip Agee, a former CIA agent, says in his whistle-blowing book, Inside the Company: CIA Diary: “At the highest level, labor operations congenial to the Agency are supported through George Meany, President of the AFL; Jay Lovestone Foreign Affairs Chief of the AFL and Irving Brown, AFL representative — all of whom were described to us as effective spokesmen for positions in accordance with the Agency’s needs.” [19]

In March 1947, President Truman, addressing a joint session of Congress, said that action had to be taken to thwart the communist guerrillas who were on the verge of taking over the Greek government. He asked for $300 million for Greece and $100 million for Turkey, declaring: “It must be the policy of the United States to support free people who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressure.” [20]

In this crisis, Brown felt he could be of special value to the United States by organizing and unifying the Greek non-communist unions. It was a difficult assignment, because the principal force among the workers were the Greek communist guerrillas, who had fought the Nazi-Italian occupation, as well as their homegrown fascists.

Also, the leaders of the non-communist unions were woefully inexperienced in the basic principles of unionism, as Brown discovered. Moreover, the communists were capitalizing on the widespread poverty, where average wages did not cover more than one fourth of the necessities of life. (After April 1947, considerable U.S. economic assistance began to flow into Greece, somewhat relieving the plight of the population.)

Brown helped to unite the non-communist unions on a program “to organize a national trade union movement free of government control and political party domination.” [21]

He also got them to agree to “seek the assistance and supervision of the AFL and the British Trade Union Congress in order to guarantee to the free trade union forces their democratic rights in the election of officers and the rebuilding of their trade union organizations.” [22]

Congress voted the money — eventually close to $700 million — and American power moved into the vacuum created by Britain in the Near East. After prolonged fighting, the Greek guerrillas were beaten, the Greek government and economy were reformed and the situation in the Mediterranean was stabilized. Brown was proud of his role in securing this victory over communism.

It is worth noting that Brown, despite his strong commitment to “free” unions, rarely criticized either the government or anti-union employers in their denial of basic rights for workers in the United States. He advocated collective bargaining between labor and management as an essential condition for a free union, but ignored the lack of it for most workers here at home. He spent a lifetime fighting the communist system, but accepted the flaws in the capitalist system that his boss, George Meany, so ardently defended.

3.3. Differing Views About Brown’s Legacy

Irving Brown, who died in Paris in 1989, evoked strong opinions from both his critics and defenders. Seth Lipsky, a Wall Street Journal reporter, wrote of Brown: “He was American labor’s leading organizer, philosopher and strategist in the vast contest waged after World War II, in which free working men vied with the communists for control of European labor.” [23]

Irving received numerous tributes from labor leaders, including AFL CIO President Lane Kirkland, who said: “We have lost a giant. No other individual did more than Irving to protect and advance worker rights in every nation and around the world.” [24]

Yet, there were critics who asserted Brown’s anti-communism served not the cause of freedom for workers but the corporate profits of international capital and the imperialist designs of Washington. He was also accused of being a CIA agent (a charge he denied), bent on destroying legitimate, independent-minded, indigenous labor unions.

A year before he died, Brown was awarded the presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, by President Ronald Reagan. In 1989, he received the AFL-CIO’s highest honor, the George Meany Human Rights Award, posthumously.

Perhaps the worst charge against Brown is not even that he accepted CIA money to try to defeat communist unions worldwide, but that all of his clandestine operations were kept secret from union members for decades, as though it was none of their business.

4. U.S. Labor Reps. Conspired to Overthrow Elected Governments in Latin America

Having emerged victorious in World War II, the United States turned its attention to its neglected “back yard,” some two-dozen mostly impoverished countries in the Western Hemisphere. Resentment against the United States had grown in many of these countries, fueled by the fact that the U.S. had been generous in its financial assistance to Western Europe, while all but ignoring the dire needs of its neighbors to the South.

The widespread poverty in these countries resulted in the rise and growth of indigenous labor unions and nationalist political parties, often led by young radicals who, to the alarm of the American government and business interests, were attracted to Communism. There was serious concern that the Soviet Union would find favorable conditions for expanding its influence and territory not too far from our southern borders.

From the outset, the AFL decided to boycott the organization of Latin American Workers Confederation, better know by its Spanish language initials, CTAL, because the call for its first convention in September 1939 was issued by the leader of the Mexican labor movement, Vicente Lombardo Toledano, a follower of the Communist Party line, who had visited the Soviet Union only two years before. Lombardo Toledano’s election as CTAL’s president provided him with leverage to influence the policies of many Latin American governments, as well as their trade unions.

To counteract the spread of communist ideology throughout the hemisphere, the AFL Executive Council in January 1946 appointed Serafino Romualdi as its official representative in Latin America, who would work for the eventual establishment of an anti-communist labor federation to rival the CTAL

Romualdi was an Italian anti-fascist, who had fled Mussolini’s Italy to come to the United States and join ILGWU’s Italian local 99 as editor of its publications. He came under the approving eye of ILGWU David Dubinsky, who felt Romualdi was well suited to take on the role of anti-communist roving ambassador for the AFL throughout Latin America, since he had traveled to most of the countries and was knowledgeable about their unions and leaders.

In April 1947, Romualdi met with Spruille Braden, Assistant Secretary of State for Latin Affairs, who fully agreed that “increasing dangers that Communist influence in Latin American labor unions represents to the security of the democratic institutions in the Western Hemisphere and specifically to the security of the United States.” [25]

Braden said that the attitude of the State Department toward the AFL’s efforts to combat Communist aggression “will from now on be not only sympathetic but cooperative.” [26] It was clear that the State Department, for reasons of its own, would be an ample source of funding and assistance for whatever campaign Romualdi would undertake.

With the urging of the AFL, the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) created the Inter-American Regional Labor Organization (ORIT) in January 1951, with a provision that unions identified as being under the direct or indirect influence of the Communist Party would be excluded. To ensure that U.S. labor would dominate ORIT, Romauldi, the AFL’s representative in Latin America, was chosen as its director.

At the founding convention, AFL’s George Meany, who was elected as a vice president, strongly asserted that no economic help would be given to any government that supported Communism or sympathized with the Soviet Union.

4.1. AFL’s Romauldi Was Long-Time CIA Agent

Romauldi, it turned out, was “the principal CIA agent for labor operations in Latin America,” says Philip Agee in his book, CIA Diary. [27] Agee worked for the Central Intelligence Agency as a field officer in Latin America for most of a dozen years. Romauldi had ties with the CIA even before he became the ORIT director and continued to serve the spy agency into the early 1960’s.

In 1950, Jacobo Arbenz Guzman was elected president of Guatemala on a program of agrarian reform in a country where wealthy families controlled most of the land and its resources. What angered Meany was that Arbenz, no Communist himself, had included several Communists in his government and supported the left-leaning Guatemalan trade unions. But his anger boiled over, as did the State Department’s, when Arbenz began expropriating the land holdings of the United Fruit Company.

A military coup, organized and financed by the CIA with Meany’s blessing, toppled Arbenz in June 1954 and replaced him with Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, who issued a decree outlawing all trade unions, not only leftist organizations.

Romualdi, who was in Guatemala during and after the coup, concedes that employers, with the connivance of the government authorities, had resorted to wholesale dismissals of every active trade unionist whom they classified as “agitators.” He says, “I found out that in the Ixcan region, workers were being paid 50 cents a day and were forced to work 81 hours a week.” [28]

Despite the torture and death of thousands of Guatemalans by right wing terrorists in the two years following Col. Armas’ takeover of the government, Romauldi still insisted that “the President himself meant well and was at heart favoring the rebirth of a healthy, free and independent trade union movement.” [29]

4.2. AIFLD Linked to Big Business and Military in Latin America

AFL-CIO President George Meany became unhappy with ORIT; there was too much squabbling among its member countries and not much was being accomplished. After nine years, ORIT ceased to exist, and in 1962 Meany set up a new international labor organization that he could control, the American Institute of Free Labor Development (AIFLD).

The new organization invited some of the most powerful American businessmen with heavy investments in Latin America to sit on its board, including representatives of Exxon and Shell oil corporations, IBM, Koppers and Gillette. It even made J. Peter Grace, head of the United Fruit Company, the biggest foreign landowner in Latin America, as its chairman.

AIFLD was now obviously committed to making the hemisphere’s impoverished countries safe for U.S. investors, with whatever means, not excluding support for military coups. It selected William C. Doherty, Jr., as its executive director, whose father had been a long-time president of the National Association of Letter Carriers and who was said to have been a CIA conduit for passing agency funds to foreign labor leaders. In his book, CIA Diary, Philip Agee describes the younger Doherty as a “CIA agent in labor operations.” [30]

In 1963, only a year after it was founded, AIFLD sponsored and funded a strike in the tiny country of British Guiana, spending over a million dollars to disrupt the local labor movement, laying the groundwork for the overthrow of the elected Cheddi Jagan government by a British military invasion

In that same year, AIFLD supplied substantial funding, strategic planning and publicity to the opponents of Juan Bosch, the legally elected president of the Dominican Republic. Two years later, 20,000 Marines landed on the island and restored power to conservative generals, with the full approval of the AIFLD.

The 1964 military coup in Brazil was backed by the CIA and supported by Brazilian unions trained by the AIFLD. Shortly after, the AFL-CIO encouraged Brazilian workers to accept a wage freeze “to bring about stability.” [31]

Appearing before Congress, Doherty explained AIFLD’s mission to the lawmakers: “Our collaboration [with business] takes the form of trying to make the investment climate more attractive and inviting.” [32] Peter Grace, head of the W. R. Grace conglomerate and then chairman of AIFLD’s board of trustees, explained bluntly that the institute “teaches workers to increase their company’s business.” [33]

AIFLD had a variety of programs to build loyalty among workers in foreign countries, which could later be exploited in the interests of American multinational corporations. With the help of CIA funding, it was able to build housing projects for workers in Uruguay that cost several million dollars and provide other AIFLD enticements to get workers to oppose the mainstream labor federation. In Ecuador, it “trained” thousands of workers in the principles of labor-management relations and the free market economy, offering money for attending classes.

In the course of its career, AIFLD is said to have “trained” 243,668 actual and potential trade union officers in virtually every Latin American and Caribbean country. Of those, more than 1,600 received special training and pay at installations in the United States.

One of AIFLD’s dirtiest covert operations was conducted in Chile in 1973, where it played a supporting role to a military junta and the Central Intelligence Agency to overthrow the elected government of Salvador Allende, who had earned the enmity of American business by threatening to nationalize Chile’s copper industry and institute a series of radical reforms. The Allende government was accused of showing sympathy for the Soviet Union.

Two years earlier, AIFLD had channeled millions of dollars to Chile’s right-wing union leaders and political parties opposed to Allende. It focused especially on developing operatives in the communications and transportation industries so that on the day the coup occurred (it happened to be Sept. 11), communication lines were left open and free for the military junta to move swiftly into action.

So pleased was AIFLD with the overthrow of Allende, that its representative in Chile, Robert O’Neill, proudly wrote to AFL-CIO headquarters in Washington that Chile had become “the first large-scale middle class movement against government attempts to impose, slowly but surely, a Marxist-Leninist system.” [34]

The AFL-CIO’s rejoicing was brief. General Augusto Pinochet, who replaced Allende, outlawed trade unions, eliminated long-established worker protections, and jailed, abducted and killed many hundreds of unionists.

5. Kirkland Built A Secret Global Empire With U.S. Funds to Control Foreign Labor

Lane Kirkland became president of the AFL-CIO at the 1979 convention when a dying George Meany called on the delegates to elect him — and no one dared say nay including several candidates who wanted the job.

Lane had very little actual experience within the labor movement. He had been a member of a tiny union, the International Organization of Masters, Mates and Pilots, remaining as a union activist for less than a year.

His passion was international relations. He earned a degree in foreign affairs in 1948 from the prestigious Georgetown University School of Foreign Services and appeared headed for a career in diplomacy.

He went to work for the AFL as a staff researcher, working in relative obscurity as a writer in the social security department until 1960, when Meany picked him as his assistant.

In Kirkland, Meany found a man as hard-bitten an anti-Communist as himself and one who would serve him well. Lane’s influence in the conduct of AFL-CIO international affairs grew, and Meany was not disappointed. His prestige and power in Washington circles also rose, but even at the height of his power, his name recognition among union members was a bare three percent.

As AFL-CIO President, Kirkland showed little interest in union organizing or collective bargaining. He said those functions and related activities were the province of the autonomous international unions. He rarely appeared on picket lines and rallies, and looked uncomfortable in a union baseball cap and windbreaker when he did.

He spent most of his time and energy to administer a world-wide labor empire through four regional institutes that he personally controlled. His operatives were active in 85 countries around the world, working to defend the policies of the United States government and American business interests.

The American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD) operated in Latin America and the Caribbean; African-American Labor Center (AALC) functioned in more than a score of African countries, ranging from Angola to Zimbabwe.

Asian-American Free Labor Institute (AAFLI) operated in about 30 countries in Asia and the Pacific, with resident representatives in Bangladesh, Indonesia, South Korea, the Philippines, Thailand and Turkey. The Free Trade Union Institute (FTUI) concentrated on European countries.

Kirkland was president of all four institutes. He placed virtually the same group of Executive Council members on the boards of all four institutes. Hardly any information about the institutes reached union members, especially those that dealt with covert operations.

While Kirkland insisted that the institutes were largely financed by the labor movement, the truth is that almost all of their funding came from the United States government and outside sources. He tried to perpetuate the myth that the institutes served as an independent voice of the labor movement.

In 1987, for example, direct grants from U.S. government agencies and the National Endowment for Democracy accounted for 98 percent of the institutes’ funding, while the AFL-CIO itself contributed a mere 2 percent toward its foreign activities.

For its lush grants to Kirkland’s institutes, the government expected them to give unflagging support for its foreign policies and the needs of American business. And the institutes were eager to oblige, because it provided them with the funds to create a global network of American-style unions, loyal to the AFL-CIO.

In the Philippines, the Asian-American Free Labor Institute (AAFLI) spent heavily to bribe leaders of the island’s Trade Union Congress to support the bloody dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, and call for a more favorable climate for American business. The institute also worked to weaken an independent union that opposed Marcos, and praised the arrests of its leaders.

A similar scenario unfolded in South Korea, where the AFL-CIO supported a government-sponsored union with substantial funding to ward off the rise of a militant independent labor federation.

While Kirkland, during the Reagan years, was plotting new strategies to extend his alliances with labor federations on four continents, unions in the United States were weakened by severe losses in membership and bargaining power.

In the 1994 Congress, when both the House and the Senate had approved the Worker Fairness Bill banning the permanent replacement of strikers, and only seven Senate votes were needed to defeat an expected filibuster, Kirkland was in Europe, attending an international labor conference.

5.1. The Endowment Replaces CIA as Grant Dispenser

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED) is a major funding agency, on which Kirkland’s institutes depended heavily for lucrative grants. It was created by Congress in 1983 to make open grants to business, labor and the two major political parties, after embarrassing scandals about illicit funding by the CIA, including the laundering of drug money.

With an annual government budget of better than $30 million, NED was able to fund a variety of social projects that equated a free market economy with democratic values and emphasized the merits of foreign investment.

AIFLD was one of NED’s favorite grantees. From 1994 to 1996, NED awarded 15 grants, totaling more than $2.5 million to the AFL-CIO institute to be used to indoctrinate Third World unions and their members to oppose nationalization of American companies, and instead, encourage investment from abroad.

Despite a law passed by Congress in 1984 that prohibited the use of NED funds to “finance the campaign of candidates for public office,” NED, through strategically-placed grants, was able to influence the election of pro-American candidates in Nicaragua in 1990 and Mongolia in 1996. It helped to overthrow democratically elected governments in Bulgaria in 1990 and Albania in 1991 and used its weight to meddle into the electoral-political processes of numerous other countries. All of these subversive activities had the approval of Kirkland and his AIFLD institute.

The Endowment, as well as the AIFLD, played important roles in the Iran-contra affair in the 1980s, with the funding of key components of Oliver North’s shadowy “Project Democracy” network, which waged war, ran arms and drugs, and engaged in other activities that violated U.S. law.

NED also mounted a well-financed campaign against the leftist insurgency in the Philippines in the mid-1980s, funding a host of private organizations, including unions and the media. And between 1990 and 1992, it donated $250,000 to the Cuban-American Nationalist Foundation and its supporters, an anti-Castro group in Miami.

It is worth noting that while Kirkland’s AIFLD was working to implement President Reagan’s policies in Latin America and the Caribbean, Reagan fired 10,000 federal air traffic controllers for daring to go out on strike.

5.2. Kirkland Applauds Victory of Polish Shipyard Workers

The 18-day strike by Polish workers at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk in defiance of the Communist government won the admiration of trade unionists around the world. The 1980 strike brought into prominence a new, militant union, Solidarnosc (Solidarity), pledged to reform the country’s economic and political system. It also made a popular labor hero of Lech Walesa, an electrician at the shipyard, who was a key figure in the historic strike.

Kirkland was delighted with the spectacular victory of the Gdansk shipyard workers. He saw the possibility of replicating Solidarity’s triumph in the countries of Eastern Europe, dominated by the Soviet Union. He felt the Reagan administration would be supportive of a campaign to liberate workers in the “Evil Empire.”

Throughout the 1980s, the Free Trade Union Institute channeled major grants to Solidarity and its supporters to meet important economic needs, using the aid to establish close ties with Walesa and other leaders.

Kirkland also saw the fall of the Polish Communist regime as an opportunity for American investors to take advantage of the country’s economic vacuum to introduce free market capitalism.

Instead of the economic improvements that workers expected from the elimination of the Communist system, there was a decline in their living standards, an increase in unemployment and a proposal for a wage freeze, as the new government wrestled with the problems of restructuring the country’s battered economy.

Six years after the strike, the Lenin shipyard was shut down as unprofitable. The new conservative government had to cope with the problem of containing “worker unrest.”

In 1989, a U.S. delegation to Poland, that included Kirkland as well as business and government leaders, suggested that the workers had to take wage cuts to provide an “important source of international competitive advantage on the world market.” [35]

Kirkland brought Walesa to AFL-CIO headquarters and honored him with a lavish testimonial dinner and the George Meany Human Rights Award. In return, he was invited to Poland, where he received a rousing welcome from Solidarity members in gratitude for the financial aid the AFL CIO had given them.

5.3. Funding Dual Unions in Russia

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1992, AFL-CIO President Lane Kirkland and his international staff created dual unions in Russia in an effort to dismember or destroy the existing mainstream labor federations.

The AFL-CIO set up a headquarters in Moscow, from which it supplied money, computers, copier machines, supplies and professional advice to fledgling “alternate unions.” It admitted that its organizing efforts were being funded by outside sources, including the U.S. Agency for International Development and the National Endowment for Democracy, with the U.S. State Department reported to have contributed $10 million to the project.

Kirkland became interested in Russian unions during the 1989 independent coal miners strike, hoping to build counterforce unions to the mainstream unions, which he characterized pejoratively as the “official” unions.

He invited leaders of the 40,000-member miners union to the 1991 AFL-CIO convention, while ignoring the General Confederation of Trade Unions (GCTU), then representing more than 100 million members in the 15 republics of the former USSR.

One of the miners’ leaders, Victor Utkin, said: “We hope that we will be strong enough to oppose the General Confederation of Trade Unions, which is composed of the old official Communist unions.” [36] The GCTU, Utkin conceded, “is very strong… They still have all the pension funds and all of the resorts and sanatoria where workers can take vacations. They own all the medical complexes where workers are treated.” [37]

Despite the AFL-CIO’s organizing efforts, the alternate unions represented about one percent of the workers, compared with the GCTU affiliates. The Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia (FITUR) had about 60 million dues-payers, while the Moscow Trade Union Federation alone had more than 4.8 million, three times as great as the largest AFL-CIO-affiliated union.

Explaining the AFL-CIO’s attitude toward Russian unions and their leaders, James Baker, Kirkland’s executive assistant, stated: “We do not recognize the General Confederation of Trade Unions as a free and independent union. It is still being run and controlled by the former bureaucrats. We have not invited them to any of our meetings and there is no intention of establishing contacts with them at this time.” [38]

For their part, Russia’s union leaders deeply resented the AFL-CIO’s unwarranted interference in their affairs.

5.4. Teachers Union Conducts Campaign to “Educate” Russians

Albert Shanker, president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), was a long-time anti-Communist and close ally of Lane Kirkland, both of whom were on the board of directors of the National Endowment for Democracy and in a favored position to get hefty NED grants.

While Kirkland was creating dual unions in Russia in the vain hope of splintering the country’s labor movement, Shanker and his aides were busy in Moscow, setting up “democracy classes” to educate Russian workers on the values and benefits of the American way of life.

Using dues money of its members, the AFT launched its Teacher Organizing and Education Resource Center in Moscow and arrogantly proposed to replace the former Russian curricula with a “democracy curriculum,” idealizing American global leadership and the virtues of capitalism, which it equated with democracy.

With $248,000 from NED, an AFT-controlled Russian language newspaper, Delo, was published, but it lasted only a year, when funds were cut in 1996.

By 1995, the known funding of the Russian operation had reached approximately $30 million. While the AFL-CIO had repeatedly refused to finance a national radio station for American workers (or a daily labor newspaper), it miraculously found, via the AFT, $660,000 for four radio stations in Russia during 1994 alone.

For a half century, American workers had been kept completely in the dark about the Meany-Kirkland covert operations in foreign countries, financed mainly by U.S. government agencies and giant corporations that expected a handsome return for their investments.

Union members were never told how, in their name, AFL-CIO leaders meddled into the internal affairs of dozens of countries, attacking indigenous labor unions and destabilizing nationalist movements that would not conform to America’s global ambitions.

Even in the historic 1995 contest for the AFL-CIO presidency, neither John Sweeney nor his rival, Thomas Donahue, discussed labor’s record on foreign policy during their debate, and it never turned up as an issue during the campaign. The prevailing view among top labor leaders was to keep the skeletons in the closet and move on.

6. Do Solidarity Center’s Covert Operations Help American Labor on Global Problems?

In his campaign for the AFL-CIO presidency in 1995, John Sweeney proposed to create a “Transnational Monitoring Project” that would work with AFL-CIO affiliates to develop organizing strategies for international campaigns and monitor global institutions like the World Bank.

This was an excellent proposal at a time when multinational corporations were moving tens of thousands of good-paying jobs to low-wage countries, and their was an urgent need for international labor solidarity. The project remained little more than a campaign promise.

Instead, the Sweeney administration established the American Center for International Labor Solidarity (1997) to replace the four regional institutes under former AFL-CIO President Lane Kirkland, whose staffs had worked with CIA agents to destabilize democratically-elected governments in the Dominican Republic, Guyana and Chile and to undermine governments that were either friendly to the then Soviet Union or hostile to American business interests.

Solidarity Center was going to be decidedly different, we were told. Its mission statement said:

“The Center provides workers and their unions with information about internationally-recognized worker rights and basic union skills training in education and organizing. We’re training public awareness of the abuses and exploitation of the world’s most vulnerable workers. We’re promoting democracy and freedom and respect for workers’ rights in global trade, investment and development policies and in the lending practices of international financial institutions. Above all, we’re giving the world’s workers a chance for a voice in the global economy and in the future.” [39]

Anyway, if you’re curious, or possibly skeptical, to know how the Center does what it says it does, they’re not about to tell you. But that’s not all. Here are some other Herculean activities that Solidarity Center boasts about:

“The Solidarity Center is preventing and resolving conflicts worldwide by breaking down race and class barriers, building relations that can bridge ethnic and racial divides and providing training and education that give workers needed job skills and the opportunity for a better future.” [40]

Does Sweeney and Barbara Shailor, the director of the AFL-CIO’s International Affairs Department, believe this self-serving hogwash? Why hasn’t anyone checked the Center’s ludicrous claims? And how come, if the Center is performing these miracles, that hardly any trade unionists in the United States even know of its existence?

6.1. Is Solidarity Center Continuing Kirkland’s Game Plan?

There are some remarkable similarities between the Solidarity Center and Kirkland’s four regional institutes. The Center gets about three-quarters of its budget from the State Department, the Agency for International Development, the Labor Department and the National Endowment for Democracy. The AFL CIO doesn’t publicize the amount of funding from each agency or what they expect from the Solidarity Center for their contributions, certainly not to promote international labor solidarity.

Like Kirkland’s “world empire,” the Center maintains offices and staffs in at least 26 countries. They include Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Croatia, Paraguay, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Venezuela and Zimbabwe. It’s not clear how the Solidarity Center’s operations in these countries have any relevance to the problems of American workers and their unions.

Solidarity’s director is Harry Kamberis, a former State Department employee, who worked for Kirkland’s Asian institute in the late 1980s, when it was involved in dirty tricks against militant unions in South Korea and the Philippines.

Kamberis and his staff continue the Meany-Kirkland policy of spending money on classes, workshops and seminars for foreign labor leaders, and providing them and their unions with substantial sums of money, office supplies and strategic advice. The goal is to attain their loyalty and unstinted cooperation in any crisis in which the American government is involved.

A major crisis came to Venezuela in April 2002, when an article in The New York Times revealed that Solidarity Center had served as a conduit for the infamous National Endowment for Democracy to deliver $154,377 to the Confederation of Venezuela Workers (CTV), whose president, Carlos Ortega, “led the work stoppages that galvanized the opposition to Mr. Chávez” — the democratically elected president. [41]

The Venezuelan labor leader worked closely with the pro-American businessman, Pedro Carmona Estanga to engineer the April 11, 2002 coup against Chavez. Carmona’s first act was to dissolve the National Assembly. But two days later, Chavez was swept back into power by the military and a tidal wave of support by the working people and the poor, much to the chagrin of the State Department. [42]

Prior to the coup, Solidarity Center invited CTV’s Ortega to Washington, knowing that he was one of the principal opposition leaders to Chavez. The AFL-CIO arranged for Ortega to visit with U.S. government officials, including representatives of the State Department, where opposition leaders met to discuss strategy against Chavez.

Available records show that even after the failed Venezuela coup, NED contributed $116,000 to Solidarity Center every three months, from September 2002 to March 2004. In return, the Center had to submit five quarterly reports containing information that its benefactor wanted.

6.2. Is Solidarity Center an Arm of the State Department?

The Venezuela incident shines a spotlight on how Solidarity Center operated behind the scenes to help subvert the freely-elected government of a country that is one of the major oil producers in the world and a target for American oil interests. It shows how bribes and favors, lavishly distributed to union activists in a poor country, can corrupt an indigenous labor movement to work against its own interests.

If this is how shamefully Solidarity Center operated in Venezuela, can we doubt that it would act in the same manner in a developing crisis in, say, Mexico, Nigeria the Philippines or any other of the countries where it maintains field offices and staff?

What is Solidarity Center doing in all of these countries, if not to serve as the eyes and ears and voice of the State Department? Should that be a function of an agency of the American labor movement?

What is especially worrisome is the tight secrecy that Solidarity Center and the AFL-CIO’s International Affairs Department maintain over their activities, hardly different from the cloak-and-dagger operations during the Kirkland years.

In the nearly ten years that Sweeney has been AFL-CIO president, the International Affairs Department has refused to publish a booklet, newsletter, press release or other material about its activities. It does not supply information, either in official union publications or on the AFL-CIO Web site. Apparently, what it says and does in our name is none of our business.

Solidarity Center provides some information on its Web site, almost all of it bragging about its highly-inflated, questionable achievements. But it offers no details about its shady, covert activities, like in Venezuela.

It is time to lift the veil of secrecy that shrouds the Solidarity Center and the International Affairs Department. American workers, suffering from the loss of tens of thousands of good-paying jobs through corporate outsourcing, should at least be kept informed about what’s happening to workers and unions in other countries, and should be told what the AFL-CIO is saying and doing in foreign affairs.

Given the aggressive efforts of multinational corporations to seek the cheapest labor markets, international labor solidarity is essential if we are not to be forced to compete with workers everywhere in a “race to the bottom.” Yet how can we establish bonds of cooperation with unions and workers in other lands if we are kept completely in the dark about what they’re doing?

It is doubtful that the AFL-CIO International Affairs Department and the Solidarity Center will change their secretive behavior, since President John Sweeney has given them his silent approval and there has been no objection from the 51-member Executive Council.

Conclusion

I decided to research and write this six-part series, “The AFL-CIO’s Dark Past,” after many California unions had waged an unsuccessful campaign for several years to get the AFL-CIO to “Clear the Air” about its covert foreign activities over the past six decades.

The International Affairs Department refused to “open the books” to reveal the sordid story of how the AFL-CIO collaborated with the Central Intelligence Agency and the U.S. State Department to overthrow democratically-elected governments and disrupt nationalist labor federations that opposed American business interests.

It is questionable whether the “dark past” has truly ended and a new era of transparency about American labor’s foreign policies has begun. There are too many similarities between the past and the present to dispel our doubts and fears.

What is needed is an independent oversight committee that will ensure that we are kept adequately informed about AFL-CIO policy initiatives and have a voice in discussing them. Since the California unions were so concerned about revealing labor’s shameful past, they ought to take the lead in a campaign for an oversight committee to ensure that it doesn’t happen again.

[1] Mike Elk, “A 98-Year-Old Labor Reporter Who Loved Avant-Garde Music” (16 September 2013), In These Times. [web]

[2] Max Cyril, “Harry Kelber, Labor Activist and Critic, Dies at 98” (2 April 2013), Workplace Fairness. [web]

[3] Ted Morgan, A Covert Life: Jay Lovestone, Communist, Anti-Communist, Spymaster (1999), p. 141.

[4] Reuther would go on to purge the UAW of Communists and pro-Communists in 1947, empowered by the Taft-Hartley Act. This marked the historical end of significant Communist influence in American organized labor. See Maurice Sugar: Law, Labor, and the Left in Detroit, 1912-1950 (1988). — M.G.

[5] Ted Morgan, A Covert Life: Jay Lovestone, Communist, Anti-Communist, Spymaster (1999), p. 179.

[6] Ted Morgan, A Covert Life: Jay Lovestone, Communist, Anti-Communist, Spymaster (1999), p. 182.

[7] Carolyn Woods Eisenberg, Drawing the Line: The American Decision to Divide Germany, 1944-1949 (1996). [web]

[8] Ted Morgan, A Covert Life: Jay Lovestone, Communist, Anti-Communist, Spymaster (1999), p. 160.

[9] Ted Morgan, A Covert Life: Jay Lovestone, Communist, Anti-Communist, Spymaster (1999), p. 165.

[10] Ted Morgan, A Covert Life: Jay Lovestone, Communist, Anti-Communist, Spymaster (1999), p. 169.

[11] Ted Morgan, A Covert Life: Jay Lovestone, Communist, Anti-Communist, Spymaster (1999), p. 197.

[12] Ted Morgan, A Covert Life: Jay Lovestone, Communist, Anti-Communist, Spymaster (1999), p. 197.

[13] Ted Morgan, A Covert Life: Jay Lovestone, Communist, Anti-Communist, Spymaster (1999), p. 223.

[14] “Labor’s Codes of Ethical Practices” (1957). [web]

[15] Anthony Carew, “The American Labor Movement in Fizzland: The Free Trade Union Committee and the CIA” in Labour History, Vol. 39, No. 4, February 1998.

[16] Ben Rathbun, The Point Man: Irving Brown and the Deadly Post-1945 Struggle for Europe and Africa (1996), p. 127. [web]

[17] Carl Gershman, The Foreign Policy of American Labor (1975). [web]

[18] John Ranelagh, The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA from Wild Bill Donovan to William Casey (1986). [web]

[19] Philip Agee, Inside the Company: CIA Diary (1975), p. 58.

[20] Truman Doctrine (1947), U.S. National Archives. [web]

[21] American Federationist, March 1948, Volume 55, Issue 3. [web]

[22] Ibid.

[23] Seth Lipsky, 17 February 1989, Wall Street Journal, p. A14. Cited in Ben Rathbun, The Point Man: Irving Brown and the Deadly Post-1945 Struggle for Europe and Africa (1996).

[24] Glenn Fowler, 11 February 1989 obituary for Irving Brown, New York Times. [web]

[25] Serafino Romualdi, Presidents and Peons: Recollections of a Labor Ambassador in Latin America (1967), p. 73. [web]

[26] Ibid.

[27] Philip Agee, Inside the Company: CIA Diary (1975), p. 544.

[28] Serafino Romualdi, Presidents and Peons: Recollections of a Labor Ambassador in Latin America (1967), p. 73. [web]

[29] Paul Buhle, Taking Care of Business: Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland, and the Tragedy of American Labor (1999), pp. 144-145. [web]

[30] Philip Agee, Inside the Company: CIA Diary (1975), p. 527.

[31] Victor G. Reuther, The Brothers Reuther and the Story of the UAW: A Memoir (1976). [web]

[32] Beth Sims, Workers of the World Undermined: American Labor’s Role in U.S. Foreign Policy (1992). [web]

[33] Ibid.

[34] Tim Shorrock, “Labor’s Cold War” (1 May 2003), The Nation. [web]

[35] Beth Sims, Workers of the World Undermined: American Labor’s Role in U.S. Foreign Policy (1992). [web]

[36] The Bulletin of the Department of International Affairs, AFL-CIO (1991), p. 10. [web]

[37] Ibid.

[38] TBD. Ibid.?

[39] Taken from a “glossy” brochure. [web] A slightly different version appears in “About the Solidarity Center” in the 2003 version of the Solidarity Center’s website. [web]

[40] Ibid.

[41] Christopher Marquis, “U.S. Bankrolling Is Under Scrutiny for Ties to Chávez Ouster” (25 April 2002), New York Times. [web]

[42] For a good, vivid account of this incident, see Kim Bartley and Donnacha Ó Briain’s The Revolution Will Not Be Televised — Chavez: Inside The Coup (2003)[web] — R. D.