Contents

- Introduction

- Women: Vulnerable and Available

- Men: Sex Power

- What MRAs Want: Hot Naked Guy With Wolf

- Macho Poses for Women

- Fascist Power

- Fetishised Power

- Disempowering Images for MRAs

Introduction

When people complain about sexually objectified images of women in advertising and other media, a typical MRA troll move is to counter that men are also sexually objectified. [1] Male models are sex objects too, says the troll: impossibly ripped and handsome studs, sexy and sexualised, a masculine ideal we can never hope to match. They should intimidate us every bit as much as female models intimidate women — but you don’t see us complaining.

The trolls are talking shite, of course, but it always helps to illustrate why. I witnessed a particularly striking illustration just yesterday, while shopping for discount undies. My favourite high-end sock emporium has two large images on display, one of a man, one of a woman, both advertising the same product: woollen hosiery. The two images face each other across the store. The models in both images are sexualised, but one is sexually objectified, and the other is not. Let’s look at the objectified image first.

Women: Vulnerable and Available

The woman sits in a vacant space, naked and vulnerable apart from her luxurious tights, her only possession and only protection. She sits below us, submissive, her chin tilted upwards. Her posture might be considered cowering or inviting or both.

One leg is drawn up towards her chest, in an almost fetal position, suggesting babyish innocence; the other leg lies open, suggesting quite the opposite. Her left arm lies between her legs, defending her genital area, but also drawing attention to it; warning but inviting. The image is designed to send us contrasting messages of immaturity and adult sexuality, hesitance and desire: an extremely fucked-up mix of signals.

With her right arm, the woman hugs herself, shielding her breasts, and drawing attention to them. Maybe this is a defensive gesture? Or maybe her naked upper body feels cold, and she’s hugging herself for warmth. Maybe she needs to be cuddled. Maybe we need to cuddle her.

The image is composed of long, curvy, yielding lines; the woman’s body seems to be pitching in the breeze, like a slender reed. The viewing perspective highlights her long legs and “cocooning” tights, but it also highlights her fragility. This is a waif-like creature; her torso appears about as wide as one of her thighs; she won’t be able to put up any resistance, whatever we decide to do.

She gazes at us directly; her expression is swooning and seductive, but the heavy eyelids also suggest sleepiness, docility. This woman is not in control of the situation, she has no agency. She’s a sex object, there to be taken. She might be afraid, she might be defensive, but you know she wants it; and besides, there’s nothing she can do about it anyway.

This is an image of feminine beauty, and it’s an image of a woman serving herself up as a sex object for an admiring viewer or predator. There is nothing unusual about this image; in fact, it’s a cliche. In Western society we’re surrounded by images just like it. These images train everyone in our society, constantly and from an early age, to think of women as objects.

Objects have no agency in themselves; they can never have agency. Objects are used, collected, traded, consumed, and desired by subjects. Objects have no value in themselves; what value they have is attached to them by subjects. The most valuable objects are the most desired ones; an undesirable object is without value. The highest aspiration an object can have is to be desired by a subject. If an object is not desired by a subject, it is worthless.

This image is aspirational; it presents an ideal that women should strive to, so that they can become desirable objects. The image tells us that luxurious tights are part of that ideal, but it also tells us a lot more. To be a desirable object, the image tells us, is to be trapped in early adolescence, to be unthreatening and needy, to be simultaneously childlike and sexually aware. The image also prescribes the physical conditions of desirability: tall, thin, young, and white — conditions that for most women are unattainable.

The stakes of being an object are high. An undesirable object has no value, it’s garbage, it might as well not be there. To prove your worth as an object, the least you must do is to acquire a token of desirability — you can buy the tights in the image, for example. But the tights will never be enough. There will always be other images, other tokens. Being a desirable object is a constant struggle, a struggle against time and nature and finances, a struggle you are ultimately doomed to lose.

Sexually objectified images like this are used to deprive women of power and agency. It’s entirely understandable that women can find them intimidating and demeaning, and that so many women fight against them. And MRAs have no business trying to piggyback their own inadequacies onto the fight, because in our society only women get sexually objectified. Images of men are very different. And to see an example, let’s turn our attention to the male model on the other side of the store.

Men: Sex Power

The image of the male sock model is an image of power.

The man is fully clothed in an expensive suit. Unlike the woman, this man has possessions: the suit, the cufflinks, the trendy minimalist sofa. He holds some kind of optical device, probably a camera, in his hand. The power of technology lies in his grasp; the instruments of human ingenuity and industry are his and under his control.

His chin tilted downwards, he examines us through the lens of the camera. There’s something cold and voyeuristic about his gaze. We get the sense that we are performing for him, on the floor at his feet. We are the objects here, and he is the subject.

The image is composed of straight lines and sharp, decisive angles. The man sits upright on his couch, at ease, confident. His right knee is erect like a phallus, his big left foot a sure sign of his phallic proportions. His wide-crossed legs give an impression of breadth and power, which are only enhanced by the viewing perspective. The man fills space, while the woman cowers from it.

He has begun to unbutton his shirt, his shoes are off, and his tie is undone. He’s going to get naked, but at his own pace; he’s in command of the situation. He’ll reveal more of himself when he wants, if he wants. He’s going to fuck, but he’ll do it when he’s ready, on his own terms. Until then, we have to keep performing for his amusement.

This is a sexualised image, but unlike the image of the woman, it depicts confident sexual power. Similar images of men can be found everywhere in Western society. From an early age, men are conditioned to identify with images like these: men are subjects, men have agency, men are in control.

There is also something aspirational about this image: we might envy this guy’s power, his looks, his suit and his socks. But for male viewers, this image is far more comforting than it is intimidating. It reassures us that as men, we are subjects. Subjects don’t have to prove their value — subjects get to assign value. As subjects, we get to decide what objects are desirable. If we desire these socks, then it’s our whim, our pleasure, our decision.

This image affirms male power. If we buy these socks, we buy into an image of male power. We as men might aspire to be this guy, but he’s just a heightened expression of what we are conditioned to feel anyway. He’s wish fulfillment, he’s an avatar, he’s what we deserve to be.

What MRAs Want: Hot Naked Guy With Wolf

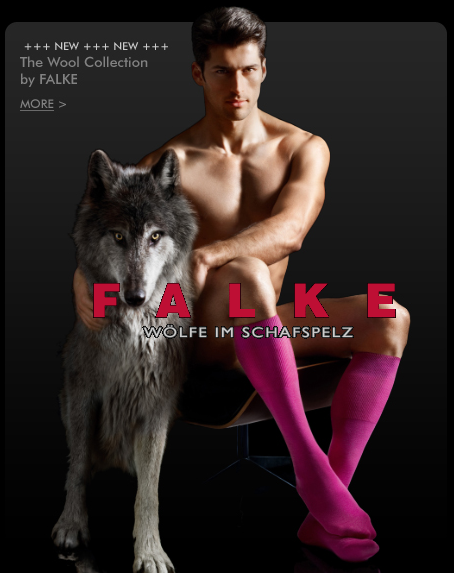

You might complain that I’m stacking the deck by comparing a clothed man and naked woman, even though that is precisely the comparison presented to customers of the sock shop. The male model is sexualised, but he’s hardly the image of raw naked male sexuality that MRAs insist they never complain about. To satisfy these guys and their cravings, let’s look at another ad from the same company, which features an actual naked buff dude.

Like the woman in the first image, this man is naked apart from his socks. But otherwise, the two images couldn’t be more different. For one thing, the man is not vulnerable; he’s muscular and athletic. He stares at us with the confident, chin-down-eyes-up [2] expression of masculine power. He sits proudly on his expensive chair, in a kind of regal slump, one arm casually resting on his knee. He is a king on his throne, entertaining our presence at his court.

This man is not fearful; on the contrary, he is dangerous. He has tamed a photoshopped wolf, a symbol of wild animal sexuality, and the savage beast is under his control. He might release the wolf on us, he might not. He is the hunter, the predator; we might be the prey.

Even stripped naked and put in pink socks, this man is not emasculated or humiliated. Quite the opposite: he radiates power and masculine energy. The man’s nakedness is brazen, unsolicited, something we have to deal with, something he makes no apology for. His pink socks become aggressively masculine; he almost dares you to call them girly. He’s man enough to wear them; are we?

The man in this image is sexualised, but he is not sexually objectified. He is a subject, he has power, he is in control. Men looking at this image are not intimidated by it, because they know that they too are subjects, in power, in control — even if they don’t feel man enough to wear pink socks.

It’s very, very, very rare in our society to see a sexually objectified image of a man, and the few such images are typically references to images of women. Such images are self-consciously subverting the norm, and are widely recognised as doing so. In this way, they tend to reinforce the norm they claim to subvert. Their selling point lies in their strangeness, their novelty value, their conjectural departure from the established power relations everyone agrees to be true. They are accepted as idle fantasies, they pose no threat.

Similarly, the images in our society which purport to depict female power are usually references to images of men. Let’s look at some of these images, taken from the same company’s sportswear ad campaign.

Macho Poses for Women

Both of these images reference familiar images of male power. The two models are muscular and athletic, they set their shoulders square, they fill space rather than shy away from it. The woman on the left has a badass chin-down-eyes-up expression; her fists are clenched, ready to take on all comers. The woman on the right stands in a contrapposto pose familiar from classical sculpture — her weight on one foot, her waist slightly coiled — a pose most often associated with Greek gods and the action-man heroes of antiquity.

On the surface, these are images of powerful women. I suspect most women would find them less offensive than the first image on this page, and if any women actually find them empowering, it’s certainly not my business to object. But I think very few male chauvinists would feel threatened by these images; quite the contrary.

For one thing, both images contain deliberate signs of weakness, little reassurances that the power of these women is not a serious threat. The woman on the left is standing on her toes; she is artifically bigging herself up, in a childish imitation of male power. The woman on the right is staring at us wide-eyed, with eyebrows arched; an expression rarely seen in male models. It’s a difficult expression to read; she might be proud, she might be startled. Her expression conveys a note of indecision and vulnerability; this woman is not entirely in control. She might have the pose and physique of a Greek god, but she still needs our patronage and protection.

More significantly, these images exist in a context, and that context is the widespread sexual objectification of women. Images like this are displayed side by side with images of women as objects to be desired and possessed and fucked. The image on the right, for example, was displayed in the same shop as the image at the top of the page, a few metres further along on the same wall.

In this context, an MRA will see these women as just more objects, objects to which he can assign a value. He might rate the women six or seven out of ten, he might decide that a confident pose and athletic physique are to his taste, or not. A woman used to regarding herself as an object might well see the images as prescribing another intimidating ideal, the athletic physique being yet another unobtainable token of desirability.

Since these images of powerful women reference images of men, they take on some aspects of the power depicted in images of men. And the power they take on is no less problematic in its new context.

Fascist Power

The images of men above depict a very particular kind of power. This power is not derived from charisma or talent or demonstrable moral advantage, and it sure as hell isn’t derived from justice or democratic consensus. Instead, the images depict a power derived from wealth, possessions, muscle, innate masculinity, the mastery of nature and technology. To put it bluntly, the power they depict is fascistic. They are images of a world where might is right.

It’s significant that the two images of powerful women above are advertising the company’s sportswear collection; fascist imagery and sports imagery are deeply intertwined. One of the earliest evangelists for what we now recognise as sport was the 19th century “father of gymnastics,” Friedrich Ludwig Jahn. Jahn was a German nationalist at a time when Germany was composed of dozens of minor principalities. Dismayed at how easily Napoleon’s armies overran these German states, Jahn and his buddies decided that the German people needed to man up a little. The new pastime of gymnastics, they were convinced, would assert the macho values needed to resist foreign invaders and build a strong, unified German nation. Gymnastics would promote a vision of healthy masculinity: muscular, proud, confident, competitive. It went without saying that these were specifically masculine values; from the beginning, women were excluded from all but the most basic gymnastic exercises.

Gymnastics clubs spread all over the German states, and their success became an inspiration for other sporting movements. Whatever their meaning in 19th century politics, the macho German nationalism they promoted had by the 20th century become a major political ingredient of Nazism. The Nazis embraced almost everything about sport: its culture of the muscular male body, its celebration of power through strength, its Darwinian competition, its victories of the strong over the weak, its deeply ingrained misogyny. They gloried in the bombast of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, which set the standard that all subsequent sports imagery strove to emulate. When you witness today’s athletic musclemen bound into a sports arena to do battle, Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana blaring in the background, you witness a thoroughly fascistic occasion in sound and appearance and essence.

Look, I watch this crap as much as anyone, and I won’t deny that there are positives to be redeemed even from sporting occasions like these. Sport has the potential to inspire wonder and confidence and progress: it has in the past given a voice to remarkable figures like Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali, who would otherwise have been unheard. But figures like this are the exception to the general rule. The culture of sport is still predominantly nationalistic, conservative, and sexist. Sports participants and fans and commentators are still predominantly men, and for most of them, their favourite sport is a welcome refuge from women. Misogynistic slurs lie ready on their lips. They celebrate the same old exclusive macho values.

While your typical MRA has no interest in women’s athletics, he has no particular trouble with images of athletic women. They’re competing on his terms, in a fight he knows his side will win. Their power is masculine power: the power of muscle, the power of the strong over the weak, the power of the fittest, the power of the school bully. It’s a power he can relate to, and tolerate. It’s fascist power.

Given the close relationship between sports and masculinity, it’s also significant that one of the athletic women depicted above is non-white. In European advertising, it’s much more common to find women of colour modelling sportswear than sex-ware. This fits the racist stereotype that women of colour are sturdier, more man-like, lacking in the feminine delicacy and refinement of white European women; a stereotype that has existed since the days plantation owners picked slaves for their healthy muscle tone. That the model above has been spared the sex-kitten treatment is hardly a victory for racial equality.

Fetishised Power

All of the images on this page are fetishistic: they promise gratification, including sexual gratification, through the objects they depict. As advertisements, the images are primarily designed to fetishise branded hosiery, but they fixate on other fetish objects, too. The images fetishise suits, gadgets, pets; they fetishise elements of the human body — feet, long legs, muscles, dreamy eyes; they fetishise reified concepts — youth, vulnerability, domination, submission, athleticism, power.

Fetishised power has different meanings for subjects and objects. For subjects, power is a means to attain sexual gratification; they find it a turn-on in itself for that very reason. For objects, power is just another token of sexual desirability, which subjects might value, or not. Since an object has no agency, it can never exercise its power freely in its own interest.

A male chauvinist looks on a sexually objectified “powerful” woman as an assembly of fetish objects. Her power is just another fetish object, something else to rub his dick on, along with her breasts, thighs, ass and face. Her power is the power of a dominatrix, and a dominatrix is every bit as objectified as a sex slave. She’s not a human subject, with agency; she cannot wield her power for her own liberation, but only for the sexual gratification of the men who objectify her. She humiliates men for their pleasure, but the ultimate humiliation is always hers, because even in power, she is disempowered.

Many images of powerful women in our society are images of dominatrices: improbable sex objects, fantasies dreamed up by males for a male audience, in which female power is objectified and fetishised and subordinated to male gratification. Imperilled superheroines in skin-tight costumes, busty barbarian babes like Red Sonja, grotesquely proportioned computer game heroines like Lara Croft and the female cast of Soul Calibur and Dragon’s Crown, dozens of other nerd-oriented “strong female characters”: all over the Web, you’ll find male fans and creators trying to sell their jack-off material as empowering to women, when the truth is closer to the opposite. [3] Which is not to say that it’s all absolutely irredeemable; if you’re a woman and find something empowering in any of that stuff, good for you. But the minds and motives behind it are far from benign, and do far more to prop up the patriarchy than undermine it.

Disempowering Images for MRAs

If the above images don’t threaten the patriarchy, what images do? I can think of one image that has been annoying bros for at least the last few decades: the image of female vocalists in mainstream chart pop. The best of these figures never sit quietly as sex objects; they won’t shut up, they insist on making themselves heard, they keep making music guys dislike, and they’re followed everywhere by intimidatingly large crowds of women. I don’t like their music either, it’s absolutely not for me, and that’s precisely why these women are so upsetting to so many of my fellow nerds: they represent one of the few remaining areas of pop-cultural output not under our total control. And so far, they have resisted male appropriation: there’s no significant equivalent of Bronyism for Beyonce. [4] [5] Pop divas remain a threat.

Another possible threat is hinted at by the noted Internet shitpit SomethingAwful.com, which tries to scare away non-subscribers with family snaps of people’s grandmothers — the idea presumably being that old women are so hideous to the eyes that people would pay anything to get them out of sight. I think we have another good candidate image here. After all, what could be more offensive to a misogynist dude than an old woman with dignity? A woman with an accomplished life, a history, relaxed in her own skin, confident in her own value? A woman who doesn’t give a fuck about putting herself on display? If we were to replace all images of sexually objectifed women with photos of beloved grannies, I would predict the following: one, society would become noticeably healthier overnight, and two, MRAs would be up in arms. They’d take to the streets for their right to objectify.

[1] MRA is an acryonym which stands for “Men’s Rights Activist.” It’s an umbrella term for communities that attempted to present men as an oppressed minority group in a world that privileged women, on the basis of talking points such as child custody, child support, and “sexual gatekeeping.” — R. D.

[2] Rocco Botte, Derrick Acosta & Shawn Chatfield, 2012-09-03. Chin Down, Eyes Up. Mega64 Comedy Skit. [web]

[3] Kate Beaton, 2011-07-09. “Strong Female Characters,” Hark, a vagrant #311. [web]

[4] S. B., 2013-02-08. Bronies and the New Sincerity.

[5] See also: Jenny Nicholson, 2020-07-21. The Last Bronycon: A Fandom Autopsy. — R. D. [web]